Blog

Subscribe

Join over 5,000 people who receive the Anecdotally newsletter—and receive our free ebook Character Trumps Credentials.

Categories

- Anecdotes

- Business storytelling

- Collaboration

- Communication

- Corporate Storytelling

- Culture

- Decision-making

- Employee Engagement

- Events

- Fun

- Insight

- Leadership Posts

- News

- Podcast

- Selling

- Strategy

Archives

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

Years

How to employ story techniques to cultivate innovation

Since early 2020, I’ve been collecting innovation stories from a global pharmaceutical company and a government science agency. In both cases, we are helping them learn from themselves by sharing stories, good and bad, of how innovation actually works in their businesses.

Sometimes these stories illustrate the struggle for innovation; that feeling of two steps forward and one step back. Where internal innovators sigh and ask, “Why do I bother?”

Then there are breakthroughs. I heard this example where a scientist, let’s call him Mike, got interested in isotope mapping 20 years ago. His colleagues and bosses thought it was a waste of time but were happy enough for Mike to explore it as long as it didn’t impinge on the rest of his work. Then one day, years into his research, he mapped his isotope data and overlaid it with known mineral deposits, and the correlation was staggering. Mike then gets a grant, but that doesn’t last forever, and interest wanes again. But he sticks at it and momentum builds. Over twenty years, Mike forges a new field of geological mapping enabling explorers to discover new mineral deposits.

Mike is quietly spoken and tells his story without fanfare. What struck me was the stories his colleagues then told, clearly experts in their own fields, about Mike’s work that showed just how proud they were of him.

These moments of sharing and hearing stories of innovation are how we learn what’s possible, what to do, what to avoid, who to work with, who to avoid, and how to get things done. But in our world of work, work, work, and now work from home, there seems to be fewer spaces to hear these stories. We need to make space for them.

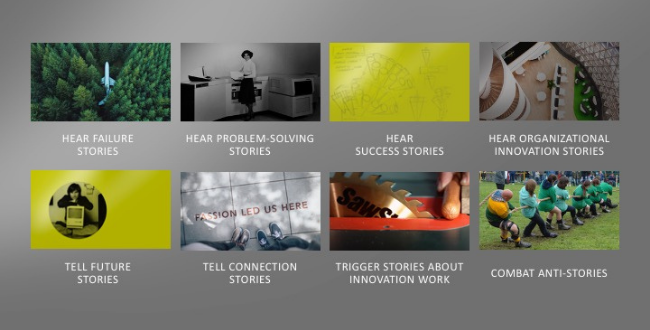

I’ve been collecting business stories now for over 20 years, and I must have heard thousands of stories, and I have seen a pattern emerging of stories innovators should hear, tell and trigger through their remarkable actions. My aim in this article to illustrate eight story-based approaches you can employ and show how simple and effective stories can be in support of innovation.

Hear failure stories

Teresa Bailey is the technical librarian at the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, California. She’s been working there for 39 years. And each week she runs story sessions in the library where project managers share their lessons learned.

I remember talking to Teresa about what happens if there is a significant failure. “Are project managers ever reluctant to talk about the missteps?” I asked. She laughed. “Absolutely,” she said. Then she told me this story.

On the 9th of September 2004, the Genesis space capsule re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere at a speed of about 28,000km per hour. At that speed, you could fly from Melbourne to Perth in 6 minutes. The Genesis space capsule was orbiting the sun for more than three years and had been collecting atoms from the solar wind. The payload was delicate, but the capsule’s trajectory meant it would land in the Utah desert. Even with its parachute, the impact might destroy the cargo.

So the Jet Propulsion Lab had a plan. It would use three helicopters, flown by Hollywood stunt pilots, to catch the chute with hooks to lower the capsule gently to the ground.

On the day the capsule was to re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere, everyone was in hangars and control rooms watching the event on monitors.

The chutes don’t open.

The capsule hurtles past the choppers and crashes into the desert.

Soon after the incident, Teresa asks the project manager, Don Sweetnam, to give a talk on what went wrong. He passes. Too early, too hurtful, shameful even. Twelve months later, however, he finally gives a talk at the library. It was a packed audience. Everyone wanted to hear the story of what went wrong. The punchline: one of the components was installed backwards causing the chutes not to open.

Failure stories are vital for innovators. We learn much more from failure than from success. But we don’t get to hear failure stories unless there is a culture to support their telling. If there’s punishment for honest attempts of improvement that don’t work out, then you are unlikely to hear the failure stories.

Hear problem-solving stories

One day, an expert photocopier technician goes to help a new team member with a problem he’s been trying to solve for a while but without any luck. The devices in question are not ordinary photocopiers but monster machines designed for high throughput. The new technician starts by telling the expert the story of what has happened so far, then they try a few things. When the machines display an E053 error, the expert groans and says, “I remember the first one of these I ever had… If it is what I think it is. I got an E053 and immediately started replacing the dead shorted dicrotrons. They were blowing the circuit breaker. But as soon as I did this, I created a 24-volt interlock problem and you can chase that one forever and never find out what it is. I happened to pull up the dC20 log and I could see I was getting hits on the XER board. It was an XER failure. So I replaced it, then the dicrotrons, and stress-tested the bugger and the real error code displayed. You can’t believe what the machine tells you.”

This story is an adaptation of one of the marvellous anecdotes Julian Orr recorded while conducting his ethnographic study of Xerox photocopier technicians for his book Talking about Machines. The stories that the two technicians tell each other establish the common ground that allows them to understand what is happening when they start diagnosing the problem. It’s impossible to notice anomalies unless you have a story that represents what to expect. Then, when something happens that doesn’t meet those expectations, a new account is needed to make sense of the latest facts. In this example, the lead technician tells a single story that holds the answer. More typically, we tell many stories to solve a problem, each one compared and contrasted with the situation at hand. Each anecdote subtly rearranges the facts until an insight emerges.

“Stories are like mental flight simulators; they allow us to rehearse problems and become better at dealing with them.”—Dan and Chip Heath, Made to Stick.

Sometimes the best problem-solving lessons come from a similar but different industry. The IT research firm Gartner has noticed that some of the best innovators actively seek out approaches from sectors that are different to them yet have similar characteristics. For example, an airport examined Disneyland’s amusement parks for insights because the objective of both businesses is to get lots of people who are milling in a confined area to line up: in one case to board a flight, and in the other to board a ride. Insights emerged for the airport when it viewed itself as an amusement park. For example, some airports are experimenting with the equivalent of Disney’s FastPass approach where people get a text to say it’s time to board.

Hear success stories

It can be a long and lonely road for an innovator. To progress, they must be inspired to push on despite the setbacks. Hearing other’s successes can be motivating. One of the great success stories in innovation is how James Dyson invented the cyclonic vacuum cleaner.

It’s 1979, and at 32 Dyson had worked on some exciting engineering projects. Right out of university, he helped design the Sea Truck with renowned British designer Jeremy Fry, a fibreglass boat that didn’t need a jetty to dock and unload goods.

His first commercial invention was the ball-barrow, a wheelbarrow that used a rubber inflated ball as the wheel.

It was while he was manufacturing the ball-barrow that Dyson got the spark to design vacuum cleaners.

Dyson was spray-painting the forks of the ball-barrow. It’s a wasteful process because most of the spray paint missed the forks and wafted around in the air.

So Dyson asked around on how to take the excess paint out of the air and discovered the best paint processes use a cyclone extractor system to suck away the waste.

He remembered seeing one of these extraction systems at a nearby timber mill that removed sawdust. So one night he hops over the timber mill fence and takes measurements of the sawmill’s cyclone extractor and then builds one in his backyard.

At about the same time, he and his wife had bought the latest Hoover, and one day while using it, he notices the suction has vanished. He empties the bag but doesn’t have a replacement, so he puts the old one back and discovers he is still without suction. When he takes a close look, he finds that all the pores in the bag are clogged with dust.

It’s then that he has a flash of insight, thinking, “What if I make a tiny cyclone extractor that could fit into a vacuum cleaner… You wouldn’t need bags anymore.”

So he made a miniature cyclone out of cardboard and scotch tape and connected it with a piece of hose to his Hoover, and it appeared to work.

He takes the idea to his company and they think he’s bonkers, so he resigns, starts his own business, and gets £50K from his mentor Jeremy Fry for 49% of the company.

He then starts prototyping in his backyard shed.

It’s just trial and error. Dyson changes only one thing and sees what happens.

He ends up building 5,127 prototypes over four years before getting it right. In 1983 he launched the Dyson G-Force cleaner.

He then pitches to the big vacuum companies like Hoover and Electrolux, and they’re not interested.

A Japanese company licences the idea and starts to build and sell the Dyson vacuum for US$2,500. It saves him from bankruptcy.

But he wants it used in the UK, and for a lot less. So he decides to build it himself. He looks for investors. No one wants in.

He ends up getting a loan from a bank for £600K, an amount unheard of today for a startup. The bank manager asked his wife whether she would be interested in a bagless vacuum cleaner, and she said she would love one. Dyson had also won a lawsuit where someone was trying to copy his patented technology, and the bank manager was impressed with his tenacity.

With four engineers and one salesman, Dyson started his company.

They sold the vacuums through catalogues to start with, but their big break came when the UK Department Store John Lewis took it on in 1993.

By 1995 it was the number 1 vacuum cleaner in the UK, and the business was making £100 million/year.

Today his vacuum cleaners are the market leaders in the US, the UK, and around the world.

Hear organisational innovation stories

Many innovators operate within a company, and the scope of innovation varies dramatically from someone working on a product like Google’s Gmail to a process innovation to improve how to send invoices to customers.

Regardless of the type of innovation, it helps enormously for organisational innovators to hear stories of how others have got things done in the company. How did they get resources, time, overcome obstacles, find sponsors, and know their work would be appreciated? Imagine if you were working for Dyson and you heard a version of the story I told above. It would give you lots of hints on how to innovate at Dyson.

And as the innovator, it would help if you also heard the cautionary tales. I collected this story from another government science agency about ten years ago.

An industrial designer came up with a new type of rifle scope that could see around corners. The designer’s manager said, “Stop wasting time with that idea, we have more important things to do.” His manager’s boss shared a similar view. One day the designer happened to wander past the Chief Scientist who was having his morning smoko. “What are you working on lad?” the chief asked. He told the chief about his rifle scope, and the chief loved it. He immediately told the Chief of Army who ordered it to be made and put in production. It was a hit.

The designer received a medal for his work, but it left egg on his managers’ faces. Despite winning a medal, the industrial designer’s career stalled.

I’m sure you can draw many lessons from this anecdote, but the sting in the tale of success was that the bosses eventually punished the designer for going over their heads. This organisation lacks a supportive culture for innovation. If you were in it, you would need to set up supports to protect you and your inventions.

I’ve said in my book, Putting Stories to Work, that if you want to change a culture, you need to change the stories told. One way to do this is to establish an organisation-wide way to share stories of innovation success. Each time an innovation story is shared, discuss it with your team and work out together what it means. Each month you share a new story, and over time everyone will understand what innovation looks and feels like.

Tell future stories

An innovator must inspire those around them about what the future could be like with the innovation. The trap is to list the characteristics of the future: we will be agile, collaborative and risk-takers. The list approach is unlikely to engage your audience, unlikely to make them feel or imagine the future. It’s better to tell future stories.

My two favourite strategies for future stories are Gibson stories, and ‘imagine this’ stories.

I was inspired by the sci-fi writer, William Gibson, who once said: “The future is already here; it’s just unevenly distributed.” I like this idea that in a large organisation somewhere the future is already happening. To turn these examples of where the future is already happening into a future story, you find one, tell it, and finish by saying something like, “And imagine if we do that across our business,” or “Imagine if we do this a thousand times.”

Gibson stories are believable because they have already happened.

When Steve Jobs launched the Macintosh, he used a type of Gibson story starting with what is happening now and projecting into the future.

“IBM wants it all. Apple is the only hope to give it a run for its money. Dealers now fear an IBM-dominated controlled future. They are turning back to Apple to ensure their future freedom. IBM wants it all and is aiming its guns on its last obstacle to industry control. Apple. Will big blue dominate the entire computer industry? The entire information age? Was George Orwell right?”—Steve Jobs, Macintosh launch, 1984.

The magical words, ‘Imagine this…’ allow us to share any illustration of the future. But a compelling future story should be vivid (you can see it happening), believable, relevant and straightforward.

Here is a future story for an insurance company that was working on innovating its technology:

So imagine this. Adam has home insurance with us and has just bought his dream car. To get his car insured, he grabs his smartphone, opens our app, types in his rego, taps two buttons, and it’s done.

Using the ‘imagine this’ approach typically involves telling a bunch of future stories to build up a more complete picture of the future.

Tell connection stories

A few years ago, we were helping an architecture firm pitch for a new building at a university. We were looking for a way for the lead architect to open the presentation and make a connection with the selection panel. So we used story-eliciting questions to draw out his experience when he told us this.

“I had just had a meeting with the Vice-Chancellor, and I was back up on the main road calling an Uber when I turned around, and I had this spectacular vista of the campus. I was admiring just how beautiful it was, so I cancelled my Uber and spent the next two hours just wondering through it, taking it all in.”

He found his connection story.

A connection story is any account we tell that gives an insight into what makes you tick, shows your values, and in this case, shows you care. A real connection happens when the listener shares a story in return. That’s you building rapport. It’s evidence you have a shared experience, and you are a bit like each other.

Innovators need to build rapport, with investors, collaborators, colleagues, anyone who has an interest in what you are innovating. Sharing your experiences will help you connect; hopefully, they will share stories with you.

Trigger stories about your work

You want people talking about your innovation. That could be investors, bosses, potential customers, possible collaborators and the media. Of course, you can tell stories about your work to inspire these stakeholders. Sometimes, however, you have to do something that will trigger stories about what you are doing.

The inventor Steve Gass had been working on a safety brake for high-speed table saws that immediately stopped the saw on contact with human flesh. Steve had already tested his invention with human-flesh stand-ins such as hot dogs, and sure enough, each time he pushed the sausage at the saw blade, it stopped, leaving the meat without a scratch. But now, with the saw spinning at 10,000 RPM, it was time to test out his invention in the way that really mattered. Gass readied himself and, with a deep gulp, pushed an index finger into the whirring blade. The saw abruptly stopped. Gass saw that his finger was unharmed and exclaimed: “It works!”

You sometimes need to do something radical to change people’s opinions. For example, in 1984, Dr. Barry Marshall discovered that bacteria caused stomach ulcers, and antibiotics could cure it. At that time, however, there was a strong belief within the medical establishment that stress caused stomach ulcers, so they opposed his findings.

So Marshall took the radical step of brewing a batch of the ulcer-causing Helicobacter pylori and infecting himself with it. Over several days, in which time he became incredibly ill, Marshall tested himself for ulcers, which he confirmed in abundance. Then Marshall drank his antibiotic antidote, and the ulcers disappeared. The media found out and reported his findings under the headline: ‘Guinea-pig Doctor Discovers New Cure for Ulcers’. Medical opinion changed overnight, and in 2005 Marshall won the Nobel Prize in Physiology.

Combat anti-stories

Inventors and innovators have to deal with naysayers. Objections get in the way of your progress, so it’s essential to know how to deal with them effectively. I like to say that for every story you tell, your audience will have their anti-stories, those negative, ‘it’s impossible to achieve what you are trying to do’ examples.

Look forward to hearing anti-stories; it means you are truly innovating.

The maxim for dealing with anti-stories is that you can’t beat a story with just the facts; you need a better story. But what examples can you use? Well if you have had some early success, then you can tell that story. James Dyson could share the anecdote of the cyclonic extraction systems he saw at the timber mill and how he built a cardboard prototype using his vacuum cleaner as suction and how it worked. This story might be enough for people to listen.

But what if you don’t have any early success yet? Then it would help if you told a story that is analogous to your situation. Imagine you are a scientist who has discovered that a virus causes high blood pressure, but no one believes you and your early results are borderline. Then you might tell the Barry Marshall story to fend off these initial objections and to give you some more time for more conclusive evidence.

Working out what the anti-stories might be to your innovation allows you to deal with them yourself. If you are talking to potential investors or stakeholders and you know their anti-stories you can say, “So you might be thinking…” then lay out their anti-story and tell your better story to combat it. Then it’s off the table and not distracting their minds.

Conclusion

As you can see, there are many ways innovators and inventors can apply story techniques to help get their job done.

Regardless of which of the eight approaches you employ, the beauty of using stories is their simplicity. You don’t need a degree to apply the techniques, and you don’t need any special equipment. And anyone can learn how to find and share them. It just comes down to noticing stories and practising sharing them, so it becomes your natural way of communicating.

This blog post builds on a section of our definitive guide to corporate storytelling, Corporate Storytelling—The Essential Guide. You can find it here (and download a convenient PDF).

About Shawn Callahan

Shawn, author of Putting Stories to Work, is one of the world's leading business storytelling consultants. He helps executive teams find and tell the story of their strategy. When he is not working on strategy communication, Shawn is helping leaders find and tell business stories to engage, to influence and to inspire. Shawn works with Global 1000 companies including Shell, IBM, SAP, Bayer, Microsoft & Danone. Connect with Shawn on: