Blog

Subscribe

Join over 5,000 people who receive the Anecdotally newsletter—and receive our free ebook Character Trumps Credentials.

Categories

- Anecdotes

- Business storytelling

- Collaboration

- Communication

- Corporate Storytelling

- Culture

- Decision-making

- Employee Engagement

- Events

- Fun

- Insight

- Leadership Posts

- News

- Podcast

- Selling

- Strategy

Archives

- April 2024

- March 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

Years

Why Communication Fails: Being Abstract

“Don’t use a five-dollar word when a fifty-cent word will do.”

—Mark Twain

In 2017, the Head of Communications for a global company attended one of our Storytelling for Leaders programs. At the lunch break, she took me aside and said, “This has been a revelation. And not just for work.”

She explained, “I recently gave a speech, representing our company, to about 100 university students. I took my 10-year-old son with me—it was an evening session and there was no one at home to look after him. He sat in the back of the hall and listened to me first, and then the government official I was introducing. He was unusually quiet during the drive home. As I was tucking him into bed that night, he gave me some feedback, ‘Why don’t you just talk normally, Mommy?’ It stopped me in my tracks.”

Nearly every text on effective communication explains the importance of plain language and avoiding overly complex words. Just one example is from the classic style manual, Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style (1979), that encourages authors to ‘omit needless words’. Yet, the world of business communication not only ignores this advice, it does exactly the opposite.

One of my favourite quotes is from William Zinsser, who wrote in 1976, “We are a society strangling in unnecessary words, circular constructions, pompous frills and meaningless jargon… Our national tendency is to inflate and thereby sound important.”1

At work, we are conditioned to use a style of communication that relies heavily on stating our views, positions and ideas using complex, impressive-sounding language—we call this the ‘assertion method’ of communication. Most people think they will be more impressive, effective and engaging by adopting this technique.

Unfortunately, in many cases, the opposite is true. A 2005 study from Princeton University showed that nearly 90 per cent of university students surveyed deliberately used complicated language to make their essays sound more valid or intelligent. The same paper revealed the folly of this: when complex language is used, audiences rated both the quality of the text and the author’s intelligence as being lower than when simple language is used.2

The human reaction

At Anecdote, we have been researching this phenomenon for the past five years and the results are conclusive. The human response to plain language using simple story structures is much more positive than when complex, abstract language is used. To test this, we show audiences two short videos of technology company CEOs introducing their company’s new strategy.

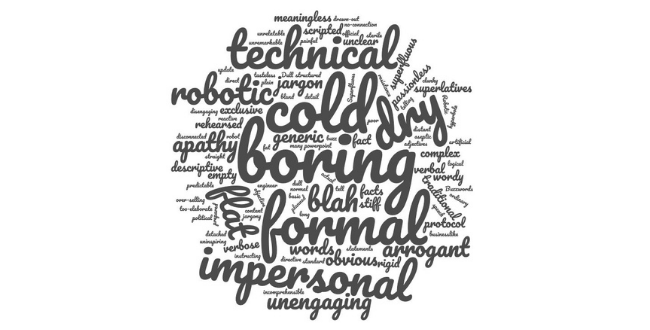

In the first video, the CEO uses complex language. Within the first 60 seconds, he uses eleven abstract phrases such as ‘efficiencies through platform-based solutions’, ‘seamless integration of essential elements’, and ‘integration with business and technology architectures’. This pattern continues through the entire presentation. We ask audiences to write one or two words that describe their reaction to the video. The responses are collated into a word cloud where the more frequent the response, the larger the word appears in the word cloud.

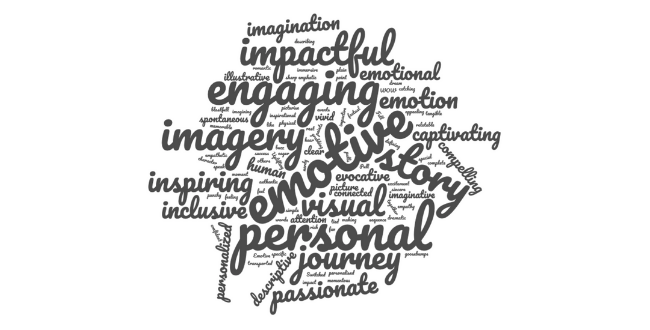

In the second video, the CEO takes us on a journey. He starts, ‘About ten years ago, we had one of our most important insights… And it’s worked well for the better part of ten years, but recently it’s broken down. Why? (He explains the problem.) So, we’ve got a great solution for this problem. (He explains the solution.)’ Even though this is a technically complex topic, and the audience are technical experts, the CEO does not use a single complex word. It’s all plain language, delivered in a simple narrative structure. Here is the word cloud for this version.

Personally, I’d much rather my audience have the second reaction. I’m confident you feel the same.

How big is the problem?

Zinsser wrote the quote above back in 1976. Things seem to have gotten worse since then. We have asked thousands of business people, both public and private sector and from organisations big and small, to respond to straightforward tasks such as ‘explain what you do for a living’ or ‘pick one of your organisation’s values and explain what it is and why it’s important’. We then ask them to objectively review their response. Over 90 per cent self-assess as using the assertion method of communicating and using overly complex and abstract words. It’s become the default mode of communication in business.

As a result, by every objective measure, our organisational communication is letting us down and demoralising our teams. Staff engagement is low and getting lower. Almost no one understands their organisation’s strategy.3 Organisations ask staff for feedback and communication is frequently the number one thing they complain about. Leaders have low credibility and staff don’t trust what their leaders tell them. And when we point these things out to leaders and communication specialists, two things generally happen. The first is that they wash it off, saying, “Everyone complains about communication, it’s just the way it is.” And the second is they merely dial-up transmission (speaking at people) and slip the corporate jargon generator into overdrive.

Improving your communication

Here at Anecdote, we are on a mission to improve business communication. The first step is to help business people realise that they have been conditioned to default to complex, abstract language and that there are alternative choices. The second step is to show them that, contrary to popular belief, using overly complex language greatly reduces the effectiveness of your communication and the audience’s impression of you.

Bad communication is a choice. You can choose to be more aware of your communication choices and their impact on your audience. Pay attention to the recommendation that lies in every decent text on communication to use plain language.

Or, to put it more simply, heed the advice of that 10-year-old boy, “Why don’t you just talk normally?”

1Zinsser, W. (2006). On Writing Well (7th ed.). Harper Collins, New York, p. 6.

2Oppenheimer, D.M. (2006). Problems with Using Long Words Needlessly. Journal of Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20, 139-156.

3Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. (2005, October). The Office of Strategy Management. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2005/10/the-office-of-strategy-management.

About Mark Schenk

About Mark Schenk

Mark works globally with senior leadership teams to improve their ability to communicate clearly and memorably. He has been a Director of Anecdote since 2004 and helped the company grow into one of the world’s leading business storytelling consultancies. Connect with Mark on: