Blog

Subscribe

Join over 5,000 people who receive the Anecdotally newsletter—and receive our free ebook Character Trumps Credentials.

Categories

- Anecdotes

- Business storytelling

- Collaboration

- Communication

- Corporate Storytelling

- Culture

- Decision-making

- Employee Engagement

- Events

- Fun

- Insight

- Leadership Posts

- News

- Podcast

- Selling

- Strategy

Archives

- April 2024

- March 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

Years

052 – Pepsi and Apple in new containers

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS

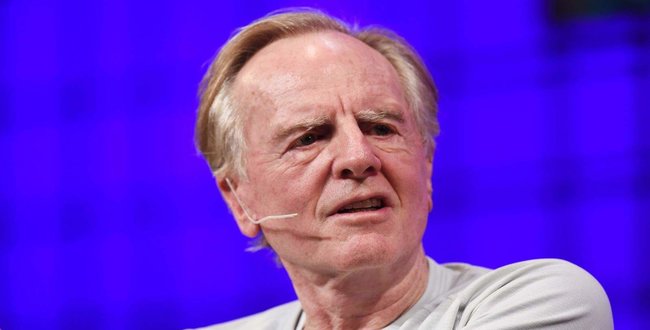

In our final episode for 2019, John Sculley, former CEO of Apple Inc., shares five stories that illustrate the importance of insight and encourage us to think differently.

2019 is drawing to a close. But before we close the office for the holiday period, we have another Anecdotally Speaking Special Edition to share with you!

Some weeks ago, Mark was lucky enough to spend an hour with John Sculley, the former CEO of Apple Inc. and former President of Pepsi-Cola, and interview him for our podcast. John shared five stories with Mark. Each story relays an experience that shaped John as a businessman, entrepreneur, and investor, and highlights the role insight can play in the success of a business. In one of the stories, John talks about this advertisement.

We thoroughly enjoyed creating this episode and hope you enjoy listening to it!

Seasons greetings for the holiday period. Anecdotally Speaking will be back with more stories that you can add to your story repertoire in January 2020.

For your storybank

Tags: competition, competitors, curiosity, data, hard work, ideas, innovation, insight, John Sculley, Steve Jobs, thinking differently

Story 1 (from 01:59)

When John Sculley was 27 years old, he was already working as the Vice President of a New York advertising agency. In 1967, he took an opportunity to join Pepsi-Cola as the company’s first MBA.

His friends couldn’t understand why he would give up his job as a Vice President to join Pepsi-Cola. At the time, Coca-Cola outsold Pepsi-Cola at a rate of 10:1.

In the 1960s, most companies outsourced their marketing efforts to advertising agencies. Very few companies had marketing departments. They weren’t sure how to use John, so he was sent off on a six-month training program. The program took John to Pittsburgh, Phoenix, and Milwaukee. He worked in a bottling plant and as a route driver. In the early hours of the morning, he helped wash and refill reusable bottles. In the middle of the night, he restocked shelves at supermarkets. He worked from summer through to winter.

His friends thought he had made a stupid decision. They compared his role to that of a truck driver. But, whatever task Pepsi-Cola gave John, he viewed it as an opportunity to learn. He learned the business from the ground up.

After his training, Pepsi-Cola gave John the jobs no one wanted. They put him in market research, so he used the opportunity to read as much as he could. Then they put him in charge of product development.

Two years passed, and there was talk of banning saccharin, a sweetener, in the US. Pepsi-Cola asked John to lead the project for reformulating Diet Pepsi.

Once John had developed a plan, he was to explain it to the Board of Directors. It was well-received. Suddenly, his profile rose within the company.

On the day the ban was announced, the CEO of Pepsi-Cola was out of the country. In his absence, John was to act as the company’s spokesperson. Suddenly, his profile rose within the industry.

The product launch was so successful that John was made the company’s Vice President of Marketing at just 29 years old.

Story 2 (from 15:14)

One of John’s first projects as Pepsi-Cola’s Vice President of Marketing was developing the first 2L plastic bottle for soft drinks.

During his first two years with the company, John had spent some time in market research. He used his experience to design an extended in-home product use test.

Every week for nine weeks, Pepsi-Cola delivered a selection of soft drinks to 550 homes. Participants could choose to purchase the drinks at a discounted price.

John and his team discovered flavour preferences. They also found that no matter how many drinks they delivered, each household’s inventory would be empty by the following week.

John thought, “If the drinks are that popular when there’s a convenient way to get them into the home, maybe we shouldn’t be focused on small bottles.”

The 2L bottles were an overwhelming success. There were huge opportunities for Pepsi-Cola in building different shelves and off-shelf displays for the bottles.

At the same time, John brought the barcode into Pepsi-Cola.

Before the barcode, the only sales records Pepsi-Cola had were tickets from transactions with salesmen. John knew, on a hot summer day, Pepsi-Co could sell an entire truckload of bottles. But, because there was no record of sales, no one else knew that.

Pepsi-Cola was the first soft drink company to put a barcode on their label, and the first to be able to tell stores how many bottles they were selling.

They could tell buyers, “By the time you pay us for a beverage, we have turned over five times in store. We are like a bank. We give you this incredible leverage of cash.” They thereby convinced buyers to put additional merchandising equipment in their stores.

Coca-Cola didn’t have a larger bottle until two and a half years later. With additional marketing efforts, Pepsi had passed Coca-Cola in popularity by 1978.

Story 3 (from 27:43)

When Steve Jobs was looking to recruit John into Apple, the pair spent 5-months getting to know each other, commuting between their respective cities each weekend.

John knew nothing about computers, but Steve was okay with that. Contrary to popular belief, Steve thought the future of computers wasn’t just that they would be smaller, more powerful, and less expensive.

Steve thought, “The future of computers is not selling millions of computers to people who are already buying them. There’s a market out there that is so much more exciting and important, and that is to sell computers to non-technical people, who know nothing about computers. That is to make computers easy to use and seductive, with so many capabilities, like graphics and media, and to enable these non-technical people to do creative things. Then, in the future, we’d be selling billions of computers.”

Steve’s competitors ridiculed him for bringing someone who knew nothing about computers into Apple. Steve, however, was confident that he needed someone different to build Apple into a consumer brand.

Story 4 (from 35:02)

Apple launched the Macintosh in 1984, announcing the launch with an advertisement during the 1984 Super Bowl.

On October 19, 1983, Steve and John saw the cover of Businessweek magazine. It said, “The winner is IBM!” Apparently, they had lost before they had even introduced their product.

Steve and John decided they needed to launch the product with something that would wake people up. They passed the task onto their creative team, who returned a storyboard ten days later. The storyboard detailed their now-famous commercial. You can watch it here.

Steve and John presented the commercial to their Board of Directors. It received dead silence.

Someone eventually asked, “You’re not going to run that, are you?”

“Absolutely, it will get people’s attention. It sets an expectation that the Macintosh is like nothing they’ve ever seen before.”

“But you don’t show a computer or explain what it is or how powerful the technology is.”

“That’s not the point. The point is to let people know that the future of computers is nothing like what it has been up until now.”

The Board told John to try to sell the advertising time they had purchased, but he didn’t try very hard. He ran the commercial anyway.

The commercial was so captivating that it was run over and over for free by television stations all across the world. Apple received an estimated US$45 million in free advertising. The commercial put Apple on the map.

Story 5 (from 45:25)

Traditionally, computer companies have earned profits by selling hardware, not software. The software was given away for free.

Bill Gates thought the future would be different. He saw computers becoming inexpensive and saw the value in their software.

Bill once told John that he practiced ‘zooming’. He would ‘zoom out’ and look beyond the boundaries of his industry, at what was happening in other industries, and connect the dots. He would then ‘zoom in’ and simplify his ideas.

Podcast transcript

Shawn:

Welcome to Anecdotally Speaking- a podcast to help you build your business story repertoire. Hi, I’m Shawn Callahan.

Mark:

And I’m Mark Schenk.

Shawn:

So this is our final episode for 2019—Christmas special if you like and we have something special for everyone. I’m going to throw it over to Mark; tell us all about it, man.

Mark:

A little while ago I was fortunate to sit down and spend an hour with John Scully. Many people will remember John Scully for his time at PepsiCo and the Pepsi Challenge; his time at Apple when he worked alongside Steve Jobs; and much more recently in venture capital/ Silicon Valley/ medical technology and improving the world using technology.

John sat down and very generously shared a whole bunch of experiences about things that have helped shape who he was. We’re going to share 5 of these stories and talk about each of them as they happen. There’s a big theme around today’s episode and that is the importance of thinking differently and how you can get insight that makes a huge difference.

So, we’ll share each story, Shawn and I will have a quick chat about what we like about it, how you can use it and how to make it even better and at the end do a bit of a wrap.

Shawn:

These stories are ones you can put straight into your pocket and retell.

Mark:

Here’s the first story. It starts way back in 1967.

John:

One of the stories that has meant a tremendous amount to me in my life was when I was a young MBA. I had been working after Wharton Business School at an advertising marketing firm in New York City. I had progressed well and become a vice-president of the agency. I was working on several consumer package good accounts and on one in particular I had the chance to do the analytical analysis of the AC Neilson market research for the Coca-Cola company.

It turned out, when I was 27 years old, that marketing in those days was being done on an outsource basis by advertising and marketing firms. Very few companies had their own marketing departments other than maybe a group in charge of PR or advertising.

I got an opportunity to join Pepsi Cola Company as their first MBA. They weren’t quite sure what to do with me and a lot of my friends couldn’t understand why I would give up a job as a vice-president of a well-known New York advertising firm to go and work for the Pepsi Cola Company.

At that time Pepsi Cola was outsold 10 to 1 in 50% of the US by Coca Cola and it was looked at as a very distant number 2 brand. My first assignment when I joined Pepsi was to go into a training programme because I was the 1st MBA that Pepsi had ever hired.

They put me on a route truck in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—this is 1967. They had me work in the bottling plant—get up early in the morning to wash bottles, refill bottles, reset supermarket shelves in the middle of the night (to avoid getting in the way of shoppers).

Then after 4 months I was sent to Phoenix, Arizona to do something similar except there it was hot in the summertime. And there I was put in charge of putting signs up on the roofs of buildings. In order to get Pepsi into the stores you had to repair the roofs as well as put the signs up. We’d have to work in the hot sun.

Then I was sent off to Los Vegas to do something similar then finally to Milwaukee where later in the year it was starting to get cold and we’d have to drive the trucks in the snow. I had to work out in a fitness club to get strong enough to take the cases of returnable Pepsi bottles down the steps into the taverns.

By this time my friends in New York thought I had made an absolutely stupid decision—why do a job like that; you have an MBA, you were a vice-president, now you’re a truck driver? I’ve always had an insatiable curiosity and whatever task they gave me I was always trying to learn as much as I could.

How many bottles were returned and refilled? How many cases would we sell in a store? Why did we have to reset the shelves in the middle of the night? Why weren’t the shelves right the first time? And I was learning the business from the ground up. After I finished my 6-month training programme I was put into the market research department and no one quite knew what I was supposed to do so I’d just go read the files.

And I read as much as I could about Pepsi Cola and soft drinks. And then I got put in charge of product development in the research labs; again getting jobs that no one else wanted. I learned a lot about how beverages were formulated and different sweeteners.

Now, it’s about 2 years later and saccharine (used in diet Pepsi and other diet drinks) was banned. The company wanted somebody to take responsibility for doing the reformulation of diet Pepsi with a different sweetener and develop the marketing and sales plan to replace the old diet Pepsi with the new reformulated diet Pepsi. I was given the job.

While I was doing that I got to be the spokesperson in front of the board of directors to explain what the plan was so suddenly my profile went up. It turned out that on the day saccharine was banned the CEO was out of the country so was the CEO of Coca Cola so I was drafted to go on the Walter Cronkite TV show and be the spokesperson on why saccharine could be replaced with another sweetener.

Suddenly I was getting attention from around the industry—who is this young man John Scully? And parallel, McKinsey and Co had been brought into to help Pepsi rethink its whole organisation for marketing and sales. The outcome of all this was that we successfully launched the new version of diet Pepsi with the new sweetener and I was drafted in to be the new marketing vice-president of Pepsi Cola Company.

I’d only been in the company 2 years at that point and obviously way over my head to get such a job. They used to call me a high-wire act because I had no particular qualifications to be a marketing vice-president (I was now 29 years old). That was my big break and as I look back on it I was given a job that most people thought was a terrible demotion from what I had been doing but during that time I was taking advantage of my curiosity and willingness to work extremely hard and I learned so much because instead of learning about the soft drink industry through a spreadsheet or sitting in meetings with staff I learned it from the ground up getting my hands dirty.

Shawn:

What an experience. All those dirty jobs that people have to do and John had a litany of examples in that story.

Mark:

Absolutely. I think that’s one of the things I liked about that story: he gave 5 examples of awful jobs he had.

Shawn:

The lovely thing is he came into it with a purpose. He was not seeing them as dirty jobs in a sense; he was seeing them as learning opportunities while his friends were going what are you doing, John? You’ve got an MBA. You were vice-president of the agency. What are you doing in PepsiCo doing these shitty jobs?

Mark:

Now you’re a truck driver.

Shawn:

That’s right—washing bottles.

Mark:

One of the points he made was he was trying to learn. One of the things I liked about it was he invested that time.

Shawn:

I thought it was good that he kept reminding us of his friends’ perspective. He’d describe some jobs and then throw in his friends’ perspective of ‘what are you doing, John?’ Then later on he does it again. I think it amps up that feeling of are you crazy, mate? This enables him to draw this thread through all the stories he tells—it’s a nice foundation.

Mark:

For sure and one of the things that all those experiences would have given him is a whole bunch of stories that he could then use in the board room introducing new ways of thinking about the business.

Shawn:

It’s a great tactic isn’t it? If you’re running any business the first thing a senior person should do is get in amongst it so you have some real life experiences that you can share. You can hardly share an anecdote if all you’ve got is a spreadsheet; it’s not quite going to hit the mark is it?

Mark:

Not anywhere near as much as ‘at 11.00pm in Pittsburgh when we were stacking shelves, this is what I saw…’

Shawn:

Exactly, it makes all the difference.

Mark:

So what about applications of that particular story?

Shawn:

The one that stands out for me is that by doing those jobs you get insight into the business. I bet a lot of those insights don’t come straight away. You do the jobs, stacking the shelves, washing the bottles, or taking the cases down the stairs but it’s probably in light of some problem later on that the insight hits you.

If I was going to tell that story I would start off with that idea you have to create the conditions for insight.

Mark:

Yeah. Another application of that story is the importance of thinking differently. As we said, this is kind of the theme through all 5 of these stories: insight and thinking differently. John finished that story by saying he learnt from the ground up doing the work getting his hands dirty; understanding the business. And I think that’s where that insight comes from.

Shawn:

This is the Tom Peter’s idea of management by walking around—similar but not exactly the same but he had these concrete experiences.

Mark:

I liked the way you said the Tom Peter’s concept of management by walking around because in 1979 when I did my first degree, Tom Peters wasn’t on the scene but management by walking around absolutely was.

Shawn:

Maybe he was just quoting someone else.

Mark:

It’s a great idea.

Shawn:

He made it popular.

Mark:

Totally. How would we make that story even better?

Shawn:

You know how we like visual elements? One of the nice visual elements of that story was him taking the crates of soft drink down the flights of stairs and he had to go to the gym to bulk himself up to be able to do this. That was a nice little touch. To me that’s a visual moment. I would like to see a couple more of those visual moments in other elements of those dirty jobs he was doing—stacking the shelves or washing the bottles.

There must have been things that happened—little moments you could tell to bring that alive.

Mark:

Zoom in on a couple of specific instances. And just amplifying that; one of the things I wanted to know when I was listening to it, right at the start when he changed from being a vice-president in New York to a truck driver for Pepsi. When he had the offer to be Pepsi’s first MBA—what happened? What was the decision –making process?

For anyone listening to this, one of the useful things to improve your stories is to ask people want do they want to know more of? Listen to the questions people ask because that gives you more insight into things they want to understand more of and you can zoom in on.

Shawn:

What do you reckon? Shall we get into the next story?

Mark:

Story number 2. The second story that John shared was some of his experiences around the things you need to do to take on a much bigger competitor and how you need to be innovative to do that.

John:

After I became marketing vice-president, one of the first things I did was to work on a new kind of package for Pepsi, which ultimately became the first 2 litre plastic bottle for soft drinks. That became one of the foundational businesses that PepsiCo got into years before Coca Cola.

The reason we did was because I had a marketing research experience (my MBA and working in the marketing research department at Pepsi). The first project I had my team work on was an extended in-home use product consumer test. We went to 550 homes and delivered to those homes every week for 9 weeks a selection of soft drinks they could choose from.

They could buy them from us; they got a discount. At the end of 9 weeks we discovered not just the flavours they picked but no matter how much they bought the previous week that their household inventory was empty the next week.

We thought about that and said ‘if soft drinks are that popular and if we can find a convenient way to get it into their homes maybe we shouldn’t just be focused on the small bottle packages we (& Coca Cola) were selling—6.5 or 12 ounce bottles. We should find a way to build much bigger bottles’.

That’s what lead to the development of the plastic bottle and it was the first major marketing programme we put into place after I became vice-president of marketing. It turned out to be an overwhelming success because not only did we sell more soft drinks but because I had been out working resetting shelves in supermarkets I realised there was a huge opportunity to build a different kind of shelves for these large sized bottles.

I realised the opportunity of having off-shelf displays and most importantly I had learned that beverages like soft drinks, beer, and dairy products—the only sales records the big chains had were these tickets (transactions directly with the salesmen) and that the majority of the marketing information that supermarkets used was coming from what they called ‘warehouse withdrawals’—meaning the majority of the products sold were going through their warehouses.

But soft drinks weren’t and I knew because I’d been out on the route trucks that on a hot summer’s day that we could sell an entire truck load of beverages in one store. No one else knew that in the supermarket business because there was no record of sales through the warehouse so they could track how much beverage was actually being sold on a hot summer’s day through an individual store.

A combination of the 2 litre plastic bottle (which we were the first to develop with Dupont) plus redesigning the beverage displays in the stores plus the new technology which was just becoming available called the universal product code (bar code) so Pepsi became the first product in America to put a bar code on the label of our 2 litre plastic bottles.

This enabled us to let the chain stores accurately know how many 2 litre bottles of beverages were being sold. Then I had to sell the idea to the chains and explain why 2 litre plastic bottles were so important. I could see the sales figures but I had to get it in a way that would really register with them because there are 40,000 different products in a supermarket.

The pitch we came up with was ‘we’re your new bank’. And they said, ‘what do you mean you’re our new bank; you’re a soft drink company?’ ‘No, you don’t understand—here are the sales records as reported by the universal product code and it turns out that by the time you pay us for the beverage that we have turned over 5 times in the store. So we’re like a bank for you because we give you this incredible leverage of cash.’

And they were amazed. We used that premise to get them to put in additional merchandise and equipment into the stores. We did all this almost 2 and a half years before Coca Cola recognised the opportunity.

When I was at the advertising/ marketing agency I had worked on the Coca Cola account and I knew from the AC Nielson tracking surveys that Coke measured physical bottles (little 6.5 ounce bottles). But in a 2 litre bottle you had about 64 ounces so we convinced AC Nielson that they shouldn’t be tracking us by physical bottle but by 8 ounce equivalents because we made our profit on selling liquid ounces.

Nielson reformatted just for us (not for Coke) and started tracking our market share on 8 ounce equivalents. It doesn’t take a lot of 64 ounce 2 litre bottles to start to get an incredible leverage in terms of the number of ounces. After 2.5 years AC Nielson awarded Pepsi with the fastest growing consumer product they’d ever measured.

Coca Cola came back at us and looking at the books couldn’t see this incredible growth in Pepsi and Nielsen said ‘yeah, because you’ve never changed from the tiny 6 ounce bottles. Pepsi switched several years ago with the introduction of the 2 litre plastic bottle to having us track 8 ounce equivalents’.

Coke went ‘oh my god’ and they quickly introduced the 2 litre plastic bottle. By that time our market share was growing exceptionally fast and we went from being outsold 10 to 1 in 50% of the country to rapidly catching up to Coke.

Then we followed that campaign with the Pepsi Challenge—a consumer campaign and by 1978 (I was made vice president in 1970) Pepsi had passed Coca Cola and was the largest selling consumer packaged good in America. The lesson there is don’t assume just doing things the way they’ve been done better is going to lead to success.

If you’re a small competitor competing with a giant company (Coca Cola in those days was regarded as the most valuable consumer brand in the world) you’ve got to change the ground rules. We changed the ground rules and a lot of the insights came from the opportunity I had to work as a trainee, driving a Pepsi truck, working in the supermarkets, working in bottling plants.

Sometimes things that don’t seem to be important for the future; if you’re curious, observe well, and willing to work hard can often become the foundation for changing the ground rules.

Mark:

I love how he finishes that by saying when you’re competing against the most valuable consumer brand in the world you’ve got to change the ground rules.

Shawn:

That’s right, you have to change everything you’re doing don’t you? If you’re doing the same thing there’s no way you’re going to make a dot of difference in that environment.

Mark:

What do we like about that one?

Shawn:

One of the things that stands out for me is it’s a series of anecdotes; an anecdote about his market research, about bringing the 2 litre bottle in, recording those sales through the AC Nielsen, the bar code. It shows that a story doesn’t just have to be one anecdote. You can put together a series of anecdotes and together they’re making your bigger point.

Mark:

Which he did very well. That’s one of the things I liked; he had a really clear point (2 clear points) around that series of anecdotes. One around the need to change the ground rules but also that the insights came from when he driving trucks and packing shelves and putting up signs on roofs.

Shawn:

Absolutely. And where would you use it?

Mark:

Again it goes back to the overall theme for this podcast: think differently and create insights. I love the insights. From the market research that people will drink as much of your soft drink as put in front of them and that led to the 2 litre bottle. Bit of a scary thought isn’t it?

Shawn:

Yeah. I’m sure that’s changed these days or maybe the insight hasn’t but maybe drinking habits have changed. To me this is a classic disruption story. To retell this I could imagine saying ‘we’re up against this bigger better competitor; let me share with you how Pepsi caught up with Coca Cola in the US.’ Then I’d tell this story. It’s one that’s good to have in your back pocket.

Mark:

I agree. There are a lot of disruption stories people commonly use and this is not one of them. This is a fantastic disruption story; Kodak, Uber, Amazon, Google, are a bit hackneyed—they’ve been used over and over. This is an additional one and very valuable.

It was very well told but one way to make this story even better is if you’re using it as a disruption story you could make it shorter and punchier.

Shawn:

I loved the way John kept making reference back to his first story. If you think of that first story as a connection story you really get an insight into his character. He’s obviously hard working, likes people, likes to get his hands dirty, takes a chance; we learn that about John just from his first story.

Mark:

Without him saying it.

Shawn:

But then he weaves in references back to that first story; it makes it very powerful. So, that’s story 2.

John:

The best story teller for turning a story into an inspirational message was Steve Jobs. When Steve was recruiting me to Apple we spent 5 months getting to know one another. Every weekend (he was on the West Coast and I was on the East Coast) and he would either come West or I would go East every weekend for 5 months. I knew nothing about computers but he wanted to recruit me (even Steve wasn’t an engineer; he was brilliant but totally self-taught). Steve had this idea back in the 80s that the future of computing wasn’t just going to be less expensive, smaller, more powerful computers. That’s what most of Silicone Valley thought.

So most people thought they would continue to sell to businesses, governments and to engineers. They weren’t thinking what can a computer really be? And Steve said, ‘no you’re all wrong’. He said, the future of computers is not selling millions of computers to the people who are already buying them but there’s a market out there that is so much more important and exciting—that is to sell computers to non-technical people who know nothing about computers and to make computers so easy to use, give it so many capabilities and make it so seductive that aren’t in today’s computers (early 80s).

Like the ability to use graphics and media to enable non-technical people to do creative things. He said if we do it well in the future we’ll be selling billions of computer enabled consumer devices. When Steve came up with those ideas Silicone Valley laughed at him; they used to call it the ‘Steve Jobs Reality Distortion Field’.

They said, ‘Steve you’re trying to violate all the laws of physics, you don’t know what you’re talking about, why would anybody want these machines?’ He was ridiculed and even more so when he recruited me to come in from the soft drink industry to be the CEO. Why would you want somebody who knows nothing about computers?

He said, ‘because I need someone to teach me about consumer marketing. I need to understand how to build computers into a big major brand’.

Shawn:

That’s such an insight. I remember when John Scully took over at Apple; I was an Apple use and wondered why get in some guy from Pepsi to take over the reins at Apple? And this does really make a lot of sense. Jobs is positioning the company to be this consumer brand and to shift the company he needed different people. Wow, that really does make a lot of sense.

Mark:

Yeah, he finished by saying that the reason Steve Jobs wanted him was to build Apple into a major consumer brand and look where he is today: job’s done.

Shawn:

Yeah. I also found it interesting that they took 5 months of meeting each other on weekends. That’s a phenomenal effort. It does show you that when you’re making a decision you really have to get to know people. You know how hopeless interviews are as a way of getting a sense of capabilities.

Mark:

It’s certainly our experience.

Shawn:

So it’s an example of that sort of effort. It’d be interesting to find out from John what actually happened in period when the board made the decision to exit Jobs out of the business. It’d be interesting as an expansion of that story.

Mark:

Another one about making that story even better would be during that process did Steve Jobs actually say, ‘do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life?’

Shawn:

It’s a simple story to share about having the insight to shift a company to selling technology to consumers who don’t know anything about technology. That is a massive shift and it’s a great little story to have in your back pocket.

Mark:

And the fact that the whole industry thought that Steve Jobs was crazy; the Steve Jobs Reality Distortion Field. Again the theme is about thinking differently and having insight and I guess thinking differently doesn’t come much bigger than re-imagining a computer company into a consumer goods company.

Shawn:

I wonder how did Jobs take himself out of that world of computing so that he could see this broader opportunity there. That’s a phenomenal skill isn’t it?

Mark:

Yep and another one on that is I’d love to dig deeper on the thought process John went through in making his decision to join Apple.

Shawn:

That’s a follow on interview.

Mark:

Of course we only had the one hour. That’s the 3rd story about the insight that led to Apple becoming a consumer brand company and recognizing that he needed to change the top people and bring in people like John Scully with the expertise in consumer brands. So what might seem a crazy idea, in hindsight was a big turning point.

The 4th story John shared with us was about a pivotal moment in Apple’s history but also in the history of advertising.

John:

Then I worked with Steve to help build the marketing branding campaign to launch the Mackintosh which we did at the 1984 Superbowl.

Mark:

Did you have a hand in that ad?

John:

Steve and I both worked very closely with the team at Chiat Day. We were sitting around on October 19th, 1983; we were still months away from launching the Mac and the cover on Business Week that day said, ‘The Winner is IBM’ and we hadn’t even introduced our product yet so we said, ‘we’ve got to do something that will wake people up—that the game hasn’t really started’.

So we started to think about what are the things that are going to happen in 1984 that could demand attention. One of the things was George Orwell said (in 1948) that 1984 was going to be an amazing year; controlled by the thought police, that the world would look a lot like it does in many parts of the world right now (invasion of privacy).

We worked with Lee Clow and Steve Hayden (heads of the client creative team) and we said we need something that’s just going to blow people’s minds when they see it. They came back about 10 days later and showed us the storyboards for the now famous 1984 commercial; a big group of zombie looking men in pyjama suits marching inline into a large auditorium.

They sit and lookup at a big screen where the thought police talking head is saying in the future we will control your lives. Then it cuts to this beautiful young girl. Everything is in a sepia greyscale except for this girl running down the aisle and she is swinging a hammer. She releases it and you see it in slow motion through the air and it hits the screen which explodes. Now on this white screen this type says on January 24th, 1984, Apple will introduce Mackintosh and 1984 won’t be like 1984.

When we showed the commercial to our board of directors there was dead silence and they all looked at me because I was expected to be the adult in the room. Everyone else was in their early 20s (average age in the Mackintosh division was 22 years old). And they said you’re not going to run that thing are you? I said absolutely; this is going to be a commercial that will get people’s attention. It sets an expectation that Mackintosh is going to be like nothing they’ve ever seen before.

They said yeah but you don’t even show a computer or talk about what it is. I said that isn’t the point. The point is to let people know that the future of computers is nothing like what it has been up until now. We were instructed by the board to try and sell the advertising time but we didn’t try that hard.

We’d spent $500,000 making this commercial; it had a lot of special effects in it. Nobody had spent $500,000 to make a commercial before except for Pepsi and Coke who made very expensive commercials. We paid just under a million dollars for the 60 second time at the Superbowl which they thought was an outrageous amount of money to spend for a one minute commercial.

The commercial ran. It so captivated the Superbowl audience (the biggest audience on TV at that time) that the commercial was run over and over for free by TV station after TV station around the country. We estimated we got 45 million dollars of free advertising.

In the meantime it put Apple on the planet. Suddenly people saw Apple as a different future with computers as personal computers. Most people didn’t even know what a personal computer was back then in 1984.

Again it was what do you have to do to change the ground rules when a small competitor is competing against a giant competitor?

Shawn:

When this ad came out I didn’t see it straight away. In Australia you don’t see the Superbowl ads. We got to see those replays that John talked about—it had that ripple effect. But it really got you going ‘what’s going on here?’ It was a surprising ad. Do you remember it?

Mark:

Yeah. Nowadays we watch the Superbowl live here in Australia and see all the ads as they occur. Back in those days it was very much a replay. People were talking about that ad.

Shawn:

There are some lovely things in this story. I really like the rich detail; John gave us the names of the creatives at Chiat Day, dates, all those facts and figures that make stories credible. As soon as you hear the facts and figure you go ‘yeah, this happened’.

Mark:

The other detail, Newsweek on 19th October running the IBM ad and that was the catalyst for them to go really big so that was a really important detail and part of that story.

Shawn:

By mentioning the links to George Orwell and other companies such as IBM you’re giving lots of possible hooks and links for the listener to bring in their own experiences. This is one of the other nice things about this story; there are so many rich hooks.

I thought too his visual description of the ad was evocative—I could really imagine it. I wasn’t sure about the pyjama suits. No, I loved it.

Mark:

One of the things I didn’t realise until he described it in words was the fact that the girl was the only thing in colour.

Shawn:

It was good. What about how you use this story?

Mark:

Again; think differently. This was really important for a computer technology company to think very differently about its advertising.

Shawn:

One of the things that struck me is if you were sitting with a group of executives and you really wanted to encourage them towards a big bang approach rather than incremental you could tell this story. If they were teetering on the edge of which way to go. There are lots of good reasons for incremental for certain things but for others you just whittle away your impact. These guys put it in one ad for a million bucks. That’s a lot of money now.

That would be evocative; you could even show a video of the ad. It could help sway a conversation.

Mark:

Another application is sticking to your guns. The board have said ‘you can’t run that; it doesn’t say anything about the technology or how good it is, it cost a lot of money’. And they ran it anyway. So using that story as an example of folks, there are times when you just need to stick to your guns.

There’s one more. Apple is famous for focusing not on the what they do but the why they do it. That ad sets the scene; it’s not the what, it’s the why we do it. And we’re doing it so that 1984 won’t be like 1984. For me another application is the importance of explaining why.

John:

I was fortunate enough to be around some really smart people who thought about things in a different way. I was sitting around with Bill Gates and Steve Jobs one evening after I had joined Apple. This was back in 1983. Bill was talking about how he was going to change the world with software. Up until that time the only computer companies were paid was on the basis of selling hardware (iron).

They gave the software away as customer service because they made the money on the iron. And Bill said that’s not the future. Bill said, in the future microprocessors will enable all kinds of inexpensive computers to be made and the value is in the software.

So Bill invented shrink-wrap software and an operating system that could be licensed out to anybody that wanted to use these new microprocessors and build computers. Just as Steve Jobs said the future is for nontechnical people to be doing amazing creative things. Everyone had the same facts in the computer industry as Steve or Bill Gates had but both of those geniuses interpreted the facts in different ways.

Steve used to tell me that you’ve got to zoom out and look beyond the boundaries of your industry and see things that are happening outside your industry, connect the dots and then when you connect the dots you zoom in and you simplify.

Shawn:

There you go; John’s just answered my question—Steve Job’s zoom out technique to see the bigger picture, connect the dots and then zoom back in and make changes in the industry. It still seems like a supernatural power of some sort but at least there is a little bit of methodology there that makes sense to me.

What do you think of that story, Mark?

Mark:

One of the things was Bill Gates was the same as Steve Jobs; he completely reconceptualised his industry and I hadn’t thought about it in that way. I found that a really insightful experience that John was sharing.

Shawn:

I guess with any of these industry redefining companies (seeing it now with Google, Amazon and Apple) you’re going to have to have this. If everyone is going one way you need to go another. We’re seeing this around privacy and just how different companies are dealing with that as well.

This is a simple story. You could go ‘I was listening to John Scully talking about sitting down with…’ and tell it from that perspective and then talk about what Gates said.

Mark:

And also how you go about disrupting an industry and the Steve Jobs experience and method; zoom out, connect the dots, zoom back in and simplify. You need to be able to do that to see the bigger picture.

Shawn:

A lot of companies suffer from this. I’ve seen businesses where they are so internally focused they wouldn’t even know what the company next door did let alone the broader industry or beyond that.

Mark:

And last week’s episode; Gold Corp and Rob McEwen’s sharing all his geographical data with the world—doing something completely unheard of to get great results. Taking the bigger picture and connecting the dots.

Shawn:

Where would you use this? Thinking differently is the key thing.

Mark:

It’s an effective story because it just made me want to ask more questions; I want to know more. When you’re telling a story that’s a really good effect to have. That was a really compact story but it left me wanting more.

Shawn:

Excellent. We’ve just listened to 5 great stories.

Mark:

From a guy who has seen some of the big turning points in the tech and consumer goods world over the last 50 years.

Shawn:

Sorry, John, just gave away ages there. That’s been fantastic; it’s given everyone a few more stories to put in your back pocket and that’s what this podcast is all about: helping you build your repertoire.

Of course, repertoire is not just built by listening to stories. You have to go out and make these stories your own and tell them to make a business point. Get out there and we’d love to hear how you go with that. Send us a message and tell us a story about what happened.

Mark:

And to help you put these stories into your story bank, in the show notes we’ll have time markers for each of the stories John shared. I’d like to finish by saying thank you very much to John for giving up his time and sharing some of these amazing experiences. We spent an hour on the phone and we couldn’t use the entire hour but he was incredibly generous.

So, John, thank you so much for sharing that and helping people across the world find and use new stories that will help them be better business communicators.

Shawn:

Thanks a lot everyone for coming on this ride, our last episode for 2019. Have a wonderful break; happy holidays and we’ll be back in 2020 to help you put your stories to work and build that story repertoire. So, until then have a great break.

About Anecdote International

Anecdote International is a global training and consulting company, specialising in utilising storytelling to bring humanity back to the workforce. Anecdote is now unique in having a global network of over 60 partners in 28 countries, with their learning programs translated into 11 languages, and customers who incorporate these programs into their leadership and sales enablement activities.