Blog

Subscribe

Join over 5,000 people who receive the Anecdotally newsletter—and receive our free ebook Character Trumps Credentials.

Categories

- Anecdotes

- Business storytelling

- Collaboration

- Communication

- Corporate Storytelling

- Culture

- Decision-making

- Employee Engagement

- Events

- Fun

- Insight

- Leadership Posts

- News

- Podcast

- Selling

- Strategy

Archives

- March 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

Years

What Kevin Hart and Brené Brown can teach us about vulnerability and humour in stories

A new type of speaker is emerging: part personal adviser, part comedian. I have two examples in mind. One is a researcher who spent 20 years studying courage, vulnerability, shame, and empathy. The other is a comedian who gained his stand-up chops in the comedy clubs of New York. The researcher starts with human insights and adds humour. The comedian begins with humour and adds human insights. We can learn from both.

Brené Brown

You might have guessed that the researcher is Brené Brown. In 2010, Brené did her first TEDx talk after returning from Hawaii where she was working with a group of Silicon Valley CEOs on vulnerability. On the flight home, she decided to ditch her academic talk and be vulnerable, to practise what she was preaching. Her presentation was a hit.

While giving her recent Netflix special, The Call to Courage, Brené admits to being a storyteller. She’d clearly spent years weaving stories into what she said. She puts this down to working with the stories she collected in her social science research. “Stories are data with a soul,” she says. My guess is that she was also immersed in storytellers while she was growing up. To be a good writer, you need to be a reader. Similarly, to be a good storyteller, you need to hear stories being told. I sense Brené has heard many stories in her life.

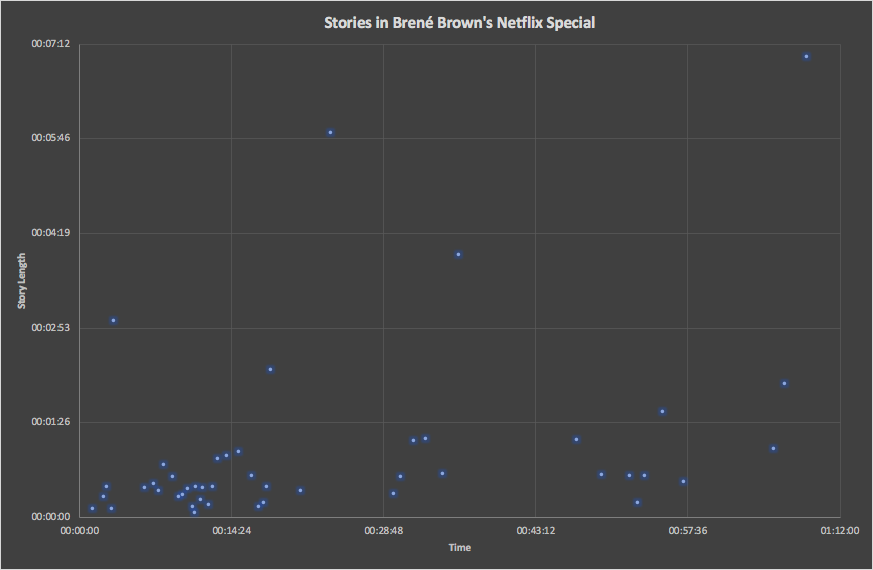

I was curious to see just how many stories Brené shared in her Netflix special. With my colleague Callum giving me a hand, I set about counting them and noting their length and when Brené tells them in the 76-minute show.

Forty-six stories. On average, that’s a story every 99 seconds. Most of Brené’s stories are under 90 seconds in length. The longest is nearly seven minutes, and the shortest is just seven seconds. Want to hear what a seven-second story sounds like? Check this out.

It was so funny. I’m backstage, they’re like, “Can we take your purse?” I’m like, “No.” It’s like totally a Texas thing, where I always have my purse and an exit plan.

Clearly, people love her storytelling style. Her TEDx talks have had millions of views on YouTube. I think her popularity was nicely summed up by a YouTube commenter who said, “Even though she’s speaking as a researcher, I find her talks touching.”

Her stories convey emotion. But we know Brené backs up her ideas with data points: 400,000 data points, according to her Netflix special. Getting the audience to feel while knowing the insights they’re hearing are backed by research, that’s a potent mix. It’s the jet fuel that has skyrocketed Brené to worldwide fame and fortune.

It’s a mistake to think you are either telling a story or you are sharing data. Some of the most potent stories also share data.

Interestingly, Brené frontloads her Netflix special with stories. She tells 34 of the 46 stories before the halfway mark—over three-quarters of the stories in total. It’s like she wants to get the audience comfortable right away by telling anecdotes, before the longer stretches of sharing her opinion and the results of her studies.

Also, by frontloading the talk with stories, Brené helps the audience understand her as a person. People want to know your character before they consume your content. As Theodore Roosevelt said, “Nobody cares how much you know until they know how much you care.”

Kevin Hart

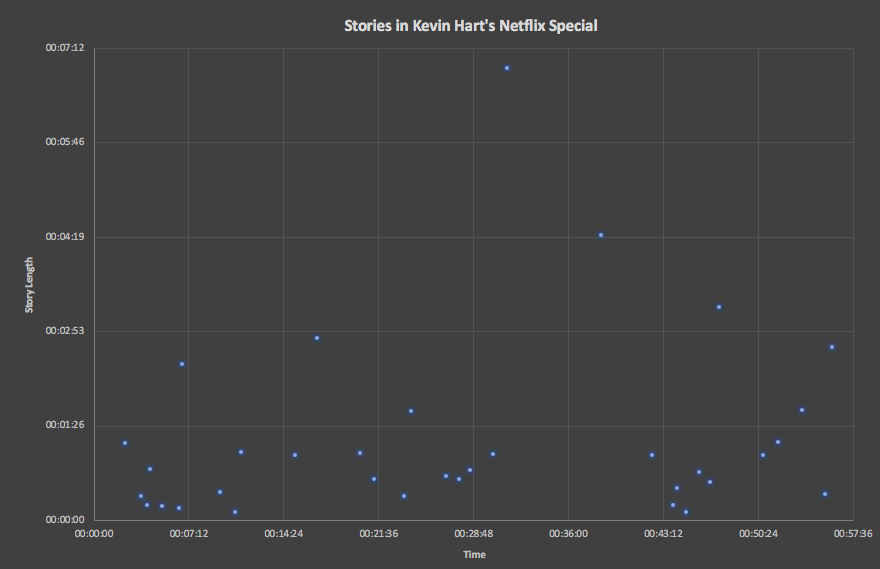

I recently watched Kevin Hart’s latest Netflix special, Irresponsible, and I was struck by how much life advice Kevin gives as a stand-up comedian. He starts with comedy and then layers in the advice, reversing Brené’s approach—she starts with the advice (based on research) and then delivers it with humour. What the two have in common, though, is that they both tell stories as their primary communication technique. And both have learned that vulnerability is a vital ingredient of success.

Kevin learned the importance of vulnerability in the early days of doing his stand-up in New York clubs. In his bio-doc, Kevin Hart, Don’t F**k This Up, Kevin recounts meeting Keith Robinson, a fellow comedian and a veteran of the business. Keith pulled Kevin aside after a set and told him that he’d seen his act several times but still didn’t know much about Kevin Hart. “You need to draw your comedy from you, so it sounds uniquely yours,” Keith said. The advice stuck.

Like Brené, Kevin tells mostly short anecdotes of less than 90 seconds. And he also frontloads his act with a rapid succession of stories.

Joe Rogan, the successful podcaster and comedian, recently commented on his show that Netflix and the other streaming services have changed stand-up specials. In the past, you would end with your best bit. In the Netflix world, you have to start with your best to hook the viewers.

Kevin hooks us from the get-go by telling a couple of stories that we find difficult to ignore. The neuroscientist John Medina, in his book Brain Rules, notes that humans pay particular attention to topics related to our survival, namely death and injury, the safety of children, and sex. Kevin, as he puts it, “gets to the sh*t” with a story about his eight-year-old son catching him and his wife having sex. He has everyone’s attention, and he is already dishing out advice.

Kevin understands universal themes, those topics that everyone in the audience has experience of and cares about: family, health, food, holidays, jobs, f**k-ups … the list goes on. But you won’t hear Kevin tell, for example, a story about a photocopy repairman and the error codes he’s getting while fixing a new machine. You can only get away with that kind of story if you’re Steve Martin—check out his classic plumber joke:

OK, I don’t like to gear my material to the audience but I’d like to make an exception because I was told that there is a convention of plumbers in San Francisco this week. I understand about 30 of them came down to the show tonight, so, before I came out, I worked up a joke especially for the plumbers. Those of you who aren’t plumbers probably won’t get this and won’t think it’s funny, but I think those of you who are plumbers will really enjoy this …

This lawn supervisor was out on a sprinkler maintenance job and he started working on a Findlay sprinkler head with a Langstrom 7-inch gangly wrench. Just then, this little apprentice leaned over and said, “You can’t work on a Findlay sprinkler head with a Langstrom 7-inch wrench.” Well, this infuriated the supervisor, so he went and got Volume 14 of the Kinsley manual, and he read to the apprentice, “The Langstrom 7-inch wrench can be used with the Findlay sprocket.” Just then, the little apprentice leaned over and said, “It says sprocket, not socket!”

Were these plumbers supposed to be here this show …?

The broader your audience, the more you should rely on universal themes. These everyday topics ensure that what you’re saying is relevant to the greatest number of people.

Brené also does this brilliantly. She could easily talk in academic detail and language. Instead, she merely mentions she has 400,000 data points and has written journal articles and books, then spends her time sharing stories that reveal the insights from her research. And rather than telling stories about the research subjects, she tells stories about her husband, holidays, swimming, and flying, all topics a broad audience gets.

Kevin and Brené also both start their stories with a relevance statement that tells us what the story is about without ruining the punchline. Here is where Kevin gets us ready for a story:

It’s very important to understand your patience. You got to know your patience levels. The older you get, the thinner your patience gets. My patience is definitely wearing thin. I know it is. You know how I know? Because I’m not the same guy as I used to be with my dogs. I’m a dog dude, people. I love dogs …

OK, we know we’re about to hear a story about Kevin being patient with his dogs. As we listen to it, we’re tuned into hearing the lesson about patience. When we hear it, the penny drops and we get a dopamine hit.

The main difference between Brené and Kevin is that Brené constructs an argument or case for vulnerability, so her stories and ideas build towards a conclusion. Kevin’s purpose is to get a laugh, and as soon as he does he moves on. One story rarely connects strongly to the next. It’s more like a casual conversation, with one story triggering the next.

Laughing and learning

Kevin Hart and Brené Brown are at the top of their game, and both are masterful storytellers. We can learn so much from them—I have only scratched the surface here. Both show us that within everyone is a strong desire to laugh and learn something, and many of these lessons and laughs come from being vulnerable. Self-effacing humour is your friend. So, consider adding your f**k-ups to your next talk. Just make sure there is a happy ending.

About Shawn Callahan

Shawn, author of Putting Stories to Work, is one of the world's leading business storytelling consultants. He helps executive teams find and tell the story of their strategy. When he is not working on strategy communication, Shawn is helping leaders find and tell business stories to engage, to influence and to inspire. Shawn works with Global 1000 companies including Shell, IBM, SAP, Bayer, Microsoft & Danone. Connect with Shawn on: