Blog

Subscribe

Join over 5,000 people who receive the Anecdotally newsletter—and receive our free ebook Character Trumps Credentials.

Categories

- Anecdotes

- Business storytelling

- Collaboration

- Communication

- Corporate Storytelling

- Culture

- Decision-making

- Employee Engagement

- Events

- Fun

- Insight

- Leadership Posts

- News

- Podcast

- Selling

- Strategy

Archives

- March 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

Years

044 – Navigating like clockwork

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS

Disregarding ideas that don’t adhere to our standard way of thinking can inhibit progress. This story illustrates the importance of having an open mind.

Here at Anecdote, we’re gearing up to turn 15 years old! We’ve been taking a trip down memory lane as we prepare for our big day. Keep an eye on our Instagram page, @RealAnecdote, for some flashbacks!

In this episode, Mark retells the story contained in Dava Sobel’s Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time. As the title suggests, the story follows John Harrison and his attempts to solve the greatest scientific problem of his time – calculating longitude. It dates back to the 1700s.

For your storybank

Tags: beliefs, bias, hard work, ideas, innovation, persistence

In 1707, four ships from a British fleet returning to England struck rocks off the Isles of Scilly. Some 2000 people lost their lives in what is now known as one of the worst naval disasters in history. Bad weather and the mariners’ inability to accurately calculate longitude caused the disaster.

In the years following, the British Parliament established the Longitude Act. The Act included a reward of £20,000 (equivalent to over US$3 million today) for anyone who discovered a practical way of calculating longitude. The Act also established the Longitude Board to choose who would receive the prize money.

Astronomy had provided a means to calculate latitude. Popular thought was that astronomy would similarly provide a means to calculate longitude. Nonetheless, one idea came from a clockmaker, John Harrison. John believed he could design and build a clock which could accurately keep time, and thereby calculate longitude. The Board gave John £500 to build his first clock, H1.

It took John 5 years to build the H1 clock. In 1736, a renowned navigator tested the capabilities of the clock at sea. The navigator was amazed by how accurate the H1 was, and by how accurately he could calculate longitude.

The Board didn’t award John the prize money but asked him to produce a more accurate clock. Again, they gave him a small amount of money to do so.

Over 17 years, John built H2, but the Board never tested the clock. An astronomer had proposed a ‘lunar distance model’ to the Board, so John’s work was sidelined. Over 40 years, John produced H3 and H4 clocks.

In 1773, John’s son petitioned the King. He asked him to recognise his father’s life work. The King soon realised that John had solved the longitude problem years before. The Board soon after paid John the full reward.

Today, we still use John’s methods for calculating longitude.

Podcast transcript

Shawn:

Welcome to Anecdotally Speaking- a podcast to help you build your business story repertoire. Hi there, I’m Shawn Callahan.

Mark:

And hi there, I’m Mark Schenk.

Shawn:

It’s great to be back on the podcast. Mark and I have been travelling around so we’ve been away from the recording studio. Is it too much to call this a recording studio, Mark?

Mark:

I think with a stretch of the imagination you could get away with it.

Shawn:

Exactly, squint a little bit and you might think it’s a studio. So, we’ve been away travelling but we’re back in Melbourne now, which is fantastic, and one of the things we’re getting ready for is our big party happening next month because our company turns 15 years old.

Mark:

Anecdote is 15.

Shawn:

So we’re having a bit of a celebration, a shindig.

Mark:

9th of August.

Shawn:

So, if you find yourself in Melbourne and you want to come along get in contact with us. We’d love to see you and hear more from our listeners of Anecdotally Speaking, so let us know.

But today we’re going to get straight into the story. Mark’s got a story for us, an historical one, and I’m going to throw it over to you, mate.

Mark:

Cool. I’ll just share the story and then we’ll talk about what we like about it, why it works and how to use it in business.

This story starts in 1707, a long time ago. The British fleet was returning to England and the weather wasn’t too good and 4 ships struck the Scilly Islands—a group of islands SW of Cornwall—so 4 warships were lost but also 2,000 lives.

It is still one of the biggest naval disasters in history and the main reason for this accident was at the time sailors were unable to accurately calculate their position at sea. For years, they had been able to calculate latitude, which is how far north or south are you from the equator but they weren’t able to accurately calculate longitude, which is the east west dimension when they were at sea.

Solving the problem of latitude was referred to as the greatest scientific problem of the age because so much depended on sea trade, and so many lives and commerce was affected by ship wrecks.

They’d known for 100’s of years that solving longitude was a problem but this naval disaster prompted a lot of action including the British parliament putting in place the ‘longitude act’. And they put in place a reward of £20,000. Now it doesn’t sound much but in 1707 it’s the equivalent of more than $3 million US today. So, it’s a huge amount of money.

And they also established a thing called the ‘Longitude Board’, which was to oversee the administration of the funding and determine who gets the prize money for someone to provide a practical solution to the longitude problem.

Lots of people heard about this and there were all sorts of ideas put forward to the Longitude Board. They were swamped with ideas. One of the ideas was from a clockmaker, a guy called John Harrison who believed that being able to keep time accurately was the solution.

And he believed he could design and build a clock that would keep accurate time and would allow longitude to be calculated. Now, Isaac Newton was on the Longitude Board and in setting up the Longitude Board he had pointed out that being able to keep time accurately at sea was a potential solution to the longitude problem but such a device was impossible.

Shawn:

They ruled it out pretty early.

Mark:

They ruled it out very early. But it was also because latitude had been solved by astronomy—reading celestial bodies, mathematical calculations etc. So, the prevailing wisdom was that longitude would also be solved by some sort of astronomical solution and that’s what they were looking for. In fact, the Longitude Board was heavily weighted towards people with an astronomical bent. The Astronomy Royale for example was one of the members.

Harrison didn’t have much education but he was a very good clockmaker. One of the clocks he made has been running continuously since 1717 in a village in England, and it’s made entirely of wood. So, he was a pretty good clockmaker.

He believed he could make this clock so he went down and presented to the Longitude Board and they funded him £500 to build his first clock, which was called H1. He spent 5 years building it. In 1736 H1 was put to sea and accurately kept time and allowed longitude to be calculated accurately on a trip to Spain and back.

Essentially, he had solved the longitude problem and proven it. The captain of the ship was amazed at how accurate Harrison’s observations and calculations were compared to the dead reckoning methods that were used by sailors at the time, even though this captain was a renowned navigator.

So, longitude solved but no. The Board didn’t award him the prize for solving longitude. What they gave him was a small amount of money to make it even more accurate. And Harrison believed he could make it more accurate. But it took him 17 years to produce his second version, H2–17 years but it was revolutionary and much more accurate.

But the Board never put that one to sea to test it and in the meantime Harrison had come up with an even better design—H3. And he developed successively more accurate clocks over a period of 40 years.

During the 1750s something happened that was really a derailer for Harrison and the chronological solution because one of the astronomers had come up with the idea of calculating longitude using something he called the ‘lunar distance model’—so looking at the moon and doing calculations off the moon.

We now know that was never going to work but it appealed to the Board and so the Board sidelined Harrison and put all their focus into this lunar distance method. Fast forward 1773, Harrison is in his 80s, he is basically a pauper. And his son petitions the King who realizes that Harrison had in fact solved the longitude problem years before and ordered the Longitude Board to pay him the full reward.

Shawn:

He finally got it.

Mark: So, he finally got recognition that he had solved the longitude problem years before. Now, it is still what you do. That’s how you calculate longitude. Harrison figured it out and solved the problem but the establishment didn’t recognise it.

That’s the story. I love the story, I love the book.

Shawn:

That book came out in the 80s or maybe the 90s? But Dava Sobel wrote that cracking non-fiction. I loved it. It’s a tiny little book isn’t it?

Mark:

Yeah, a tiny little book; very easy to read. Dava Sobel—if you haven’t read the book: Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time—it’s a great book.

Shawn:

So, what do we like about that story? The thing that stands out for me is there is a real problem and lives were at risk. Lives were lost through not being able to solve this problem. And there’s also this element of a clear good and bad guy.

You’ve got Harrison there who is just this carpenter who makes clocks, low socio-economic, low status guy and in the hierarchy of the UK his class is much lower than the guys on the Longitude Board.

Mark:

Yes, working class versus the elite.

Shawn:

Exactly. So, you’ve got that dynamic set up. It’s always good to have a good guy and a bad guy.

Mark:

Certainly it makes a big difference. So many stories throughout history are about a good character overcoming a bad character. We shouldn’t get caught up in the whole good guy, bad guy thing.

One of the things I like about it is it’s a lesson from history and that same lesson is being repeated over and over.

Shawn:

Exactly. There are some nice elements there too about the persistence this guy has had to build all these different versions of the clock even though he’d essentially done enough work to win the prize after his first clock.

Mark:

A bit of a perfectionist was Mr Harrison.

Shawn: In some ways he was probably his own worst enemy in the sense of ‘hey, I’ve got another good version for you. Don’t worry about that one, look at this one, this is even better’. Maybe that’s part of it as well.

Mark:

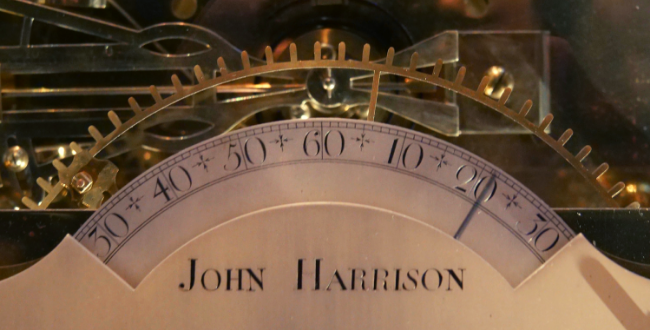

I love the fact that you can go and see these clocks at the Greenwich Observatory in London.

Shawn: Yes, they are spectacular too. I was surprised too when I saw them just how small H2, 3, and 4 are. They’re almost like big fob watches.

Mark:

I wouldn’t want to carry them.

Shawn:

No, you wouldn’t want to carry them around in your pocket but they’re not as big as what you’d imagine a clock to be. You can tell he took the idea of the pocket watch as a form factor—ok how can I make something that will withstand the water, the temperatures, humidity, and all the other things that are going to happen on a ship back in the day.

Mark:

When I was there, H4 wasn’t there but the other three were so I’ve got a few photos so maybe we’ll use some of those photos. One of the things I liked about it was it was a novel solution. The problem had been around for ages and he came up with a novel solution to the problem.

Shawn: And quite a simple solution really, except for the fact that he had to create new techniques and use all sorts of different things to make it happen but as an idea it was a very simple idea.

Mark:

The idea was simple but the bringing it to life took many, many years.

Shawn:

You might say something too about the importance of execution. You have a simple idea that’s going to get the job done but it’s actually in the detail of the execution that will challenge you more than anything else.

Mark:

When Steve Jobs was interviewed about when he came back to Apple he talked about it having fallen into a disease where it thought having great ideas was enough. And he killed off most of the ideas because there was lots of ideas generation but very little product creation.

So he said, ‘no, no, no, we’re going to pick the best ideas and we’re going to turn them into products’. So that’s the big thing: ideas to execution.

Shawn:

So, they’re some of the things we like but how would we make this story even better? You told one version. Are there any other ways you could tell it?

Mark:

I think it’s a very good example of how you can use a story effectively but only when you know what the point is. Because I told that without trying to make a point and we see this all the time in business where people have a really good story and they tell it but the way to make it better is to be absolutely clear on what point you’re trying to make in that moment.

Shawn:

Yeah, that’s right because if you’re trying to make that point around how easy it is for the predominant power to diss and disregard the crazy guy coming in from left field. So, if you told that story you could just zoom straight into ‘there was this guy, Harrison, in the 1700s, solving this problem using clocks and doing it in a totally different way. And you tell it from that perspective it would shorten the story considerably.

Mark:

So I guess that’s one of the ways to make it even better; it to pick a point that you want to make with that story, and we’re going to talk about that in a minute—the points you could make with it.

Shawn:

I don’t think it’s as straightforward as that. I think you could tell that full story but it depends on the context. If you were standing up giving a presentation and you wanted to make these bigger points (you might want to make a couple of different points) but you would tell that whole story just the way you told it, with imagery so you could see Harrison, the clocks, and all that sort of stuff.

When you command a stage you have so much more flexibility but if you’re sitting around a table of 6 business leaders and you want to make a point, there is no way you’re going to tell that story.

Mark:

You do not have the latitude; you don’t have the time.

Shawn:

You’re lucky to have a minute to be able to give a thumbnail version of that story to be able to get the idea across.

Mark:

You’d probably get the opportunity to go ‘that idea sounds a bit like what Harrison was facing back in the 1700s when he solved the longitude problem’. And people would say, ‘what do you mean?’ So you might get a minute.

Shawn:

Exactly. The other thing that would enhance that story is to have a little bit of a character thumbnail of Harrison—what does he look like. We kind of know it; he was this guy in the Midlands of England, probably had a different accent to everyone else down south for example. You’d say just a little bit but enough to give an image of the guy.

Mark:

Of course. I didn’t do any of that, I just launched into ‘Harrison was a clockmaker’. I guess the little segue about the clock that’s still running in England does give some insight into his character, the sort of guy that he was, and that he was a very good clockmaker. He had an eye for the long term.

Shawn:

And he was already doing amazing stuff.

Mark:

So, how might we use that story in a business context?

Shawn:

We’ve touched on the innovation one haven’t we? You know, easily knocking ideas because they don’t adhere to the standard way of thinking so there’s that element of it.

Mark:

It’s a great one if you’ve got an organisation where you wanted to encourage innovation and you wanted people, managers in particular, to listen to the ideas from their teams.

Shawn:

Especially to those people you see as outliers.

Mark:

So, what you’d said about the crazy lone guy. He could actually be the one who’s giving you the best possible advice because everyone else is going ‘astronomy, astronomy’; Harrison’s going ‘clock’. So, that’s a good one.

You could also use it to demonstrate the diversity of thinking. If you’ve just got a bunch of astronomers who are trying to solve the longitude problem, you’re probably not going to get very far so you need different ways of thinking, different backgrounds, from completely different walks of life.

Shawn:

Yes, that’s right. If you’re putting together a team, it’s unlikely in the first blush that you would say, ‘we’ve got this longitude problem; we’ll get the mathematicians and astronomers in. Shall we get a carpenter in?’

Mark:

Let’s get a clockmaker.

Shawn:

But that’s the sort of thinking you have to have and it rings true for today.

Mark:

And there are so many great examples of how diverse teams are so much more effective at coming up with ideas and generating and executing solutions than non-diverse teams and that story illustrates that.

Shawn:

I think there’s something around persistence. Here you’re got a guy who is a tinkerer. He loves to get the new version out. He’s not going to stop. He’s not going to say, ‘I’ve nailed it’ cause he’s got a better idea and he wants to improve it.

I did hear a nice little anecdote about Steve Jobs where the designers had just finished their ultimate version of the iPod with the click wheel and all that lovely Jony Ive’s sort of design and aesthetic.

Mark:

I still have one of those.

Shawn:

Have you? I think if you have it in the original packaging that would be ideal. But they took it to Steve Jobs, very proud of what they’d done and he looks at it. He’s pretty impressed but he says, ‘can you make it smaller?’ ‘No, we’ve used these components; we’ve cramped it down to the smallest amount’.

Steve Jobs grabs the iPod walks over to the fish tank and drops it in. And bubbles appear from the device and he just says, ‘we can make it smaller’. Those designers must have been shaking their heads.

But at the same time, the feedback you hear is that even though he was pushing and pushing them and at the time it grated with them, they look back at that time in history as some of the best work they’ve ever done.

Here’s a guy who obviously has that built in; he’s pushing himself. He has that ability so it’s a great example of that.

Mark:

And as he learned more and developed more, some of the things he invented to make the clock to solve the longitude problem, particularly through H2, H3, H4, they’re still in use today.

He was getting more and more experienced; just think if he’d lived another 20 years. What could he have done?

Shawn:

He could have done the digital clock.

Mark:

He could have done the iPod. The importance of iteration—that’s another potential business use.

Shawn:

And experimentation. Well, I think it’s time to give it a bit of a rating. It’s my turn to give it a rating in terms of usefulness. I actually heard this story told in a business setting for the first time when I worked in the Cynefin Centre at IBM and Dave Snowden used to tell this story, usually around this idea of where ideas come from, and be careful you don’t have that group that’s squashing ideas.

And I could see, told in that setting, people were on the edge of their seats just hanging off every word of the story so I know it’s a good one so I’m going to give it an 8 out of 10. I think this is a solid story that can be used in all sorts of different ways.

You can tell along version like you did or you can tell a short version as well. What about you? Do you think you could have this one in your back pocket?

Mark:

I do. I have it in my back pocket; I love it. And I particularly the against the odds aspect of it. I’m going to go with 8 as well.

Shawn:

Wow. Two high scores for us. We don’t get many 9s or 10s do we?

Mark:

No.

Shawn:

We’re a bit tough on ourselves.

Mark:

Hard task masters.

Shawn:

Well guys, it’s been great sharing another business story with you. I think we’ll wrap things up unless there’s anything else.

Mark:

Just a reminder about our birthday party. We’re really excited it’s going to be a big party so please, if you’re in town let us know and you’re welcome to come along.

Shawn:

That’ll be terrific. Well, thanks for listening to Anecdotally Speaking and tune in next time for when we share another episode of how you put these stories to work. Bye for now.

About Anecdote International

Anecdote International is a global training and consulting company, specialising in utilising storytelling to bring humanity back to the workforce. Anecdote is now unique in having a global network of over 60 partners in 28 countries, with their learning programs translated into 11 languages, and customers who incorporate these programs into their leadership and sales enablement activities.

Comments

Comments are closed.

This question of clocks vs. astronomy is touched on in “Gunpower and geometry” by B Wardhaugh. He points out the clock was very expensive and very fragile, whereas the lunar method relied on a few shillings worth of books and some tedious but easily do-able calculations. A ship-master is going to go for the cheapest option.

If Harrison had been able to mass produce his device he may have stood a better chance.