Corporate Storytelling—The Essential Guide

By: Shawn Callahan, Mark Schenk, Mike Adams, Paul Ichilcik

The Story-Powered Organisation

The definitive

guide to corporate storytelling in 2023.

Don’t have time to read the whole guide right now? No worries. Let us send you a copy so you can read when it’s convenient for you.

Just let us know where to send it (takes 5 seconds).

What is corporate storytelling?

Corporate storytelling, also called business storytelling, is the purposeful and systematic application of story techniques in an organisation to deliver business outcomes.

Here’s a simple example. A large insurance company wants to ensure its strategy sticks. It wants its leaders to have the strategy in their heads so they can act strategically day in, day out. So the leaders work together to develop a story that explains their strategy; their strategy story. The very process of developing the story ensures that everyone owns what’s created. Then the top 150 leaders learn how to tell it orally—without notes, just in their own way, adding their own anecdotes—and they teach their direct reports how to tell it. Now they can all explain their strategy without having to fire up PowerPoint or refer to a plan-on-a-page document. Employee engagement soars because people feel confident their leaders know where they are heading, and that they’re all heading in the same direction.

There are many corporate storytelling techniques. Often, these involve leaders learning how to find and share stories to improve how they communicate with their people or those outside the business. But corporate storytelling is much more than that. For example, salespeople are now learning story skills to close more business faster. A company can use stories to define its brand or to communicate its strategy. Apple and The Ritz-Carlton share stories daily with their people to improve customer service. Stories are also used to share knowledge, to inspire action, and to change minds. We are seeing story techniques being used in just about every part of the enterprise.

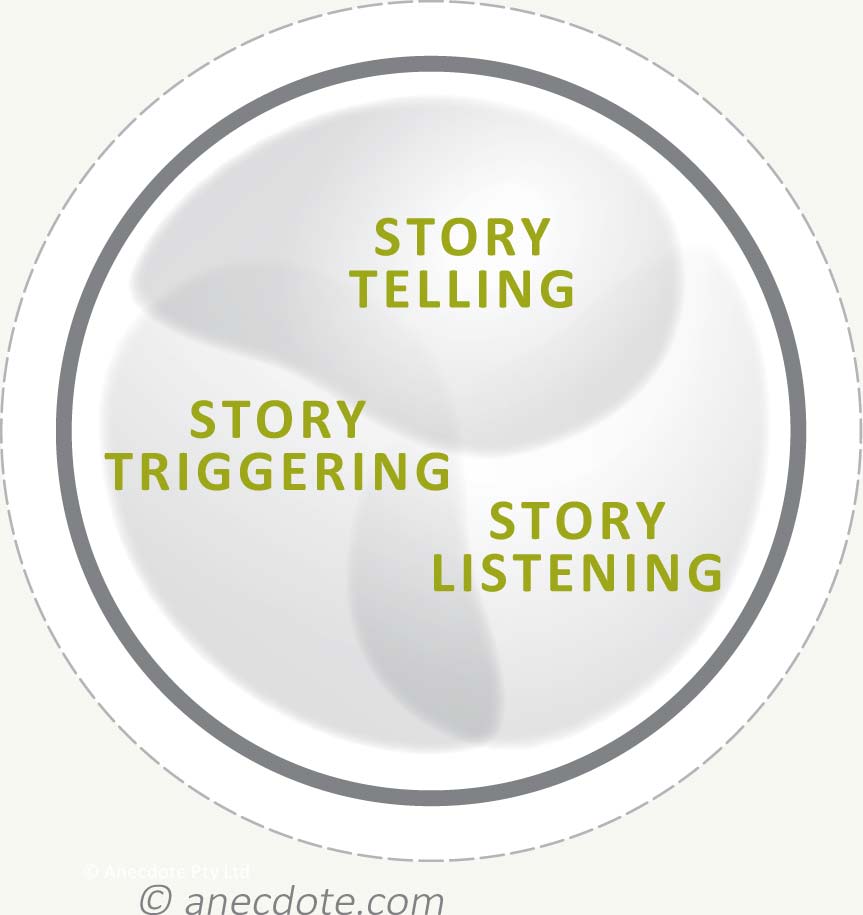

There are also many ways in which companies apply these story techniques and they go beyond just story-telling. Companies are systematically finding stories using story-listening methods, and the very astute are discovering ways to trigger new stories by taking remarkable action that people will share stories about. Taken together, these stories define an organisation’s brand, illustrate its leaders’ collective character, and constitute its culture.

In this article, we list the most popular ways in which businesses are utilising story techniques. For each business topic, we describe the business problem companies are typically trying to solve, and how story initiatives work in this context. We also point to some resources so you can learn more.

Leadership communication

“There have been great societies that did not use the wheel. But there have been no societies that did not tell stories.”

—Ursula Le Guin, novelist

The business problem

Leaders want and need to be heard, and it’s vital that what they say sinks in and makes sense. Ideally, what they say results in people taking action. Leaders need the ability to stand up and deliver their message (without notes) supported by examples (stories) that increase the message’s authenticity, meaningfulness, clarity, and memorability.

Here’s what can happen when a leader tells a story.

A large professional service firm in Hong Kong was transitioning to a new CEO, and for a while the outgoing CEO stayed on to help with the changeover—both executives served as joint-CEO for a few months. During this time, they had to present to a town hall meeting. The outgoing, experienced CEO stepped on stage and asked, “Have you seen the movie Hidden Figures?” Heads nodded. “It’s about a group of black American women in the 1960s working for NASA as human computers. They do the calculations, by hand, for the moonshots.”

The CEO continued: “Well, the head of the human-computer pool, Dorothy Vaughan, notices that a new IBM computer is being installed. She knows this is a threat, a disruptor, to their work, so she heads down to the city library and gets a book on the FORTRAN programming language and teaches herself how to program the IBM computer. Then she teaches the pool of human computers she supervises. They become the first programmers at NASA.”

The CEO then said, “So what’s our FORTRAN? How are we going to respond to the disruptors we are seeing in our industry?” They then continued their talk.

Next, it was the new CEO’s turn. He gave the standard presentation replete with slides of graphs and tables of utilisation rates, revenues and profits.

After the town hall meeting, the experienced CEO was inundated with people saying they’d met with their teams and had ideas on what their FORTRAN was. They were excited and keen to make a difference. The new CEO heard nothing from nobody.

Leaders seek out story skills when they lack inspiration, when briefings have become boring or tedious, or when they’re having trouble persuading their audiences. They also look to storytelling when they feel they are being too abstract or they’re waffling, not making their point clearly.

In addition to general leadership communication, there are specific scenarios that benefit from story techniques, such as making a strategy stick, delivering an effective pitch, and embedding values (these topics are discussed later in this article).

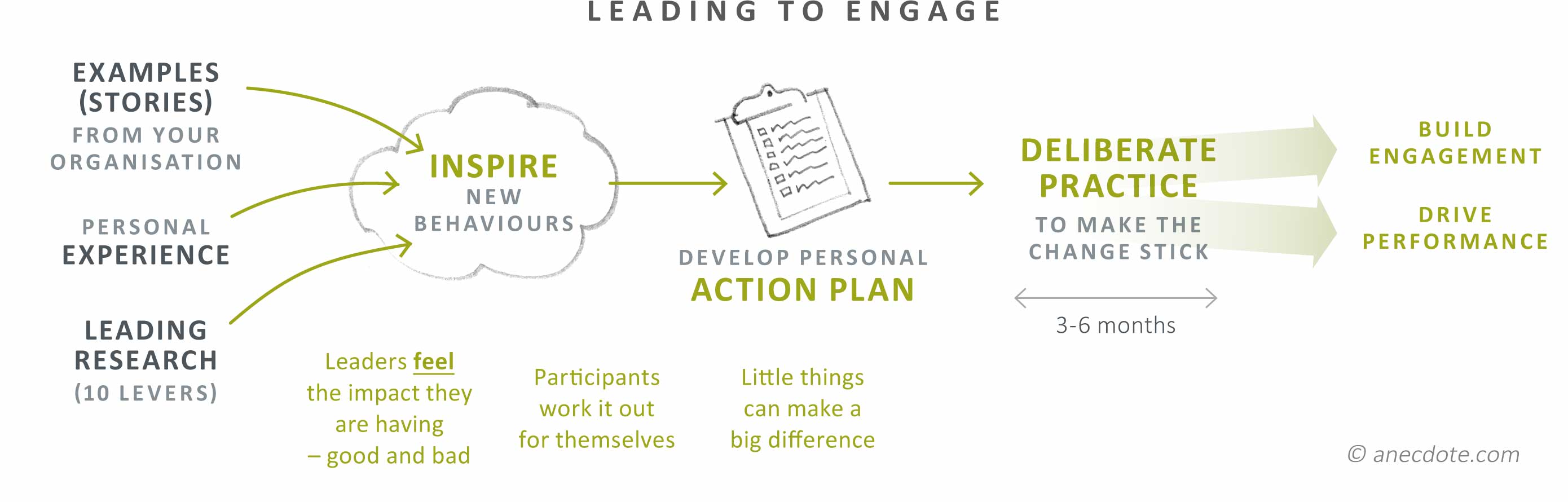

The typical solution

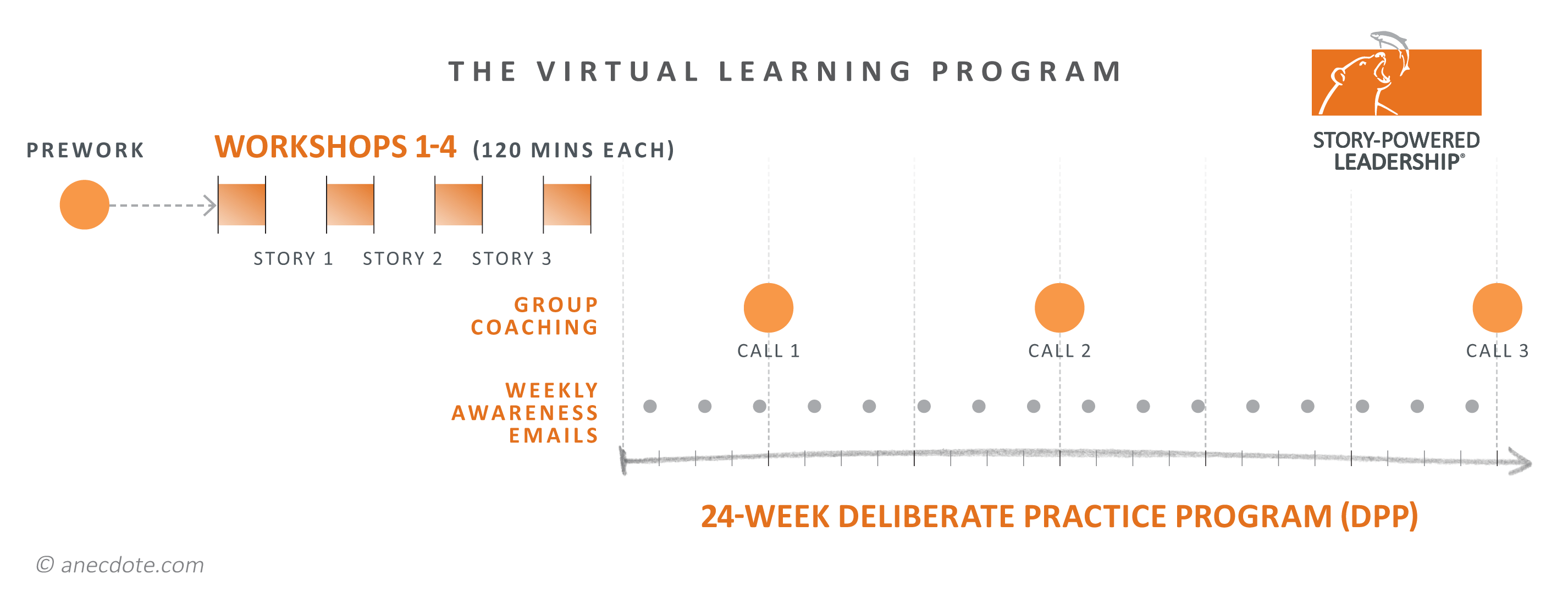

Companies often invest in training their leaders in storytelling. Because storytelling is a practice, not just content to be learned, it’s vital that the training is practice-based and is delivered over an extended period (2–6 months) so there is time for the leaders to apply what they learn, get feedback and try again.

Hybrid learning models are popular where there are face-to-face or virtual instructor–led components, online learning modules, smartphone-based practices and feedback activities, teleconferences and peer coaching. Here’s how we deliver our virtual version of Story-Powered Leadership.

Coaching is also effective. For a group of leaders, a combination of individual and group coaching sessions enables them to work on specific presentations and meetings they have in their schedules whilst also learning from their peers and learning how to coach each other.

Resources

Sales communication

‘In our old sales training workshops, we used to teach sellers to ask sequences of questions in a particular order. The goal was to diagnose the buyer’s problem with a bias towards the seller’s solution. In retrospect, it’s clear why that wasn’t effective for most sellers.’

—Mike Bosworth, author of Solution Selling and What Great Salespeople Do (with Ben Zoldan)

The business problem

Sales communication can be split into two basic categories. One is transactional sales, where the buyer needs only basic information such as price, features and benefits to make a buying decision. Transactional sales are increasingly the preserve of e-commerce and won’t be discussed further in this article.

The other category is complex sales, which require an in-depth conversation between buyer and seller for the purpose of problem-solving. The critical business issue with complex sales is that so few people are good at the problem-solving conversation. Studies show that, compared with transactional sales, the majority of salespeople fail to do well in complex sales situations.1

In fact, the major outcome of classic sales conversation training seems to be legions of salespeople who sound just like, well, salespeople—those spouting predictable salesy questions and phrases that make them sound insincere and turn their buyers off. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that many top-performing salespeople are unaware of their skills or the reasons for their success, as can be seen in the following example.

In 2017, Matt, the founder and managing director of a successful commercial real estate business, became ill and was unable to keep working in his business. The sales results slipped alarmingly, which is when Matt asked for Anecdote’s help.

When we met Matt, the first thing we noticed was his stories—he’s one of those rare stream-of-consciousness storytellers. In short order, Matt told an hilarious story about his father and grandfather in the real estate business, then another about having been the top salesperson in an international real estate company before setting out on his own. And then, pointing to a building across the street, he told us a story about it!

Curious, we asked Matt whether his salespeople knew and could tell stories like the ones he’d just told. Matt reflected for a moment and then said, ‘No. They don’t tell stories.’

So we set about teaching Matt’s sales teams how to spot and tell stories. We helped them collect the best company stories and put them in a sales story bank. Now, Matt’s company is no longer reliant on him to close critical sales deals because his sales teams have learnt his storytelling skills and are able to leverage the company’s best stories.

The best sellers are storytellers because they understand that buying decisions are both rational and emotional, and that the best way to spark an emotion that leads to action is with a story.

The typical solution

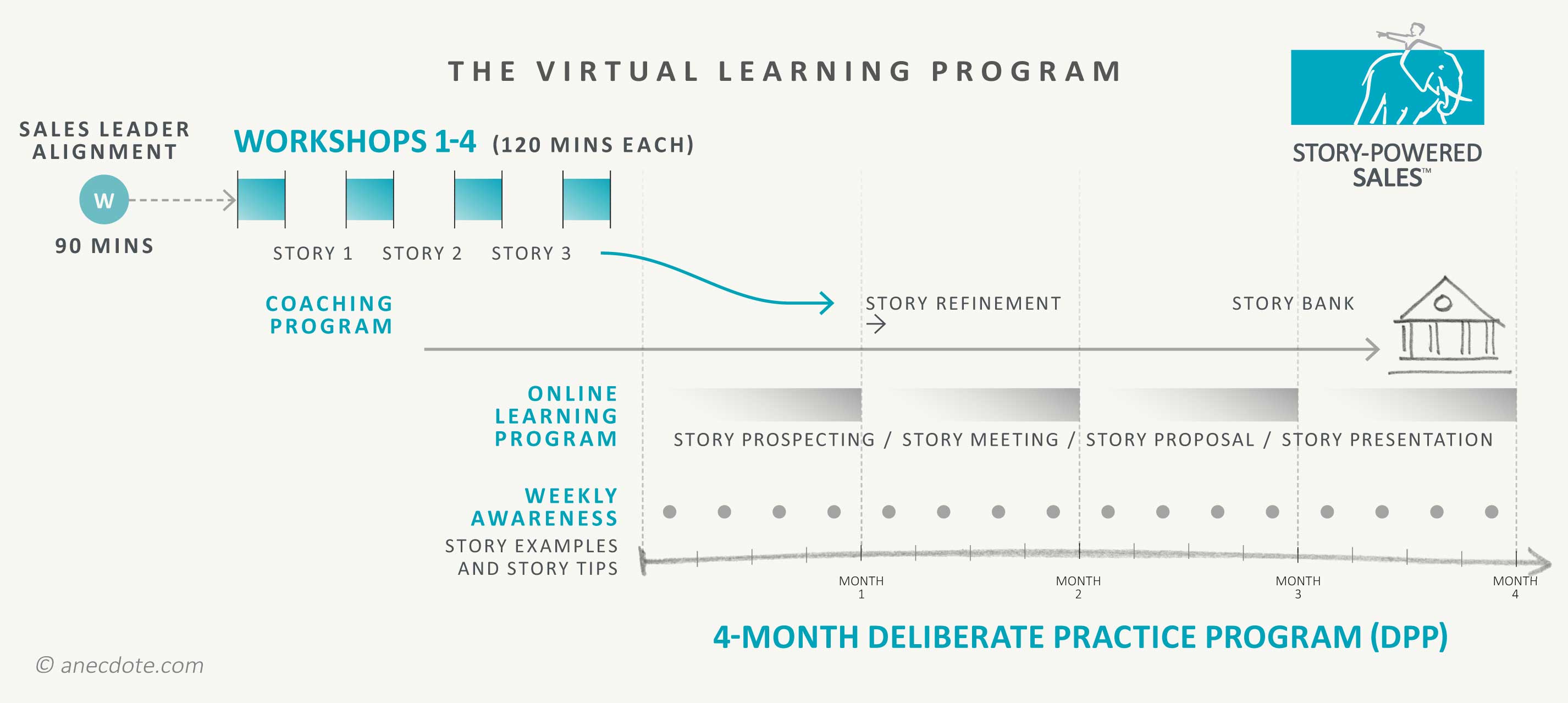

Companies can invest in storytelling training programs and ongoing coaching for their sales teams. The programs cover the sales story frameworks and include group exercises for finding and telling connection stories to quickly build rapport, stories to sell change, and stories to help close a deal. Crucial also is learning the art of story listening, because complex problems are best understood with an exchange of buyer and seller stories.

A typical storytelling program involves virtual or face-to-face workshops with the team, followed up with individual coaching so that each salesperson becomes confident in finding and telling their own stories. Here’s how we deliver our virtual version of Story-Powered Sales.

For the storytelling program to stick, it’s important that stories are captured and stored in a sales team story bank for use by current and new salespeople.

Specialised coaching to help sales leaders become story coaches and incorporate story work in their routine team management is also often necessary.

1 Dixon, Matthew and Brent Adamson (2011). The Challenger Sale: Taking Control of the Customer Conversation. Penguin. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Challenger-Sale-Control-Customer-Conversation/dp/0670922854

Resources

Strategy development and communication

‘A company without a story is usually a company without a strategy.’

—Ben Horowitz, entrepreneur and investor

The business problem

Companies spend a significant amount of time and money, often with large consulting firms, to develop their strategy, then mistakenly think they’ve passed the finish line when the strategy is complete. In fact, the race has just begun. Communicating and embedding the strategic choices become the big jobs that determine the success of any strategy. An effective strategy is in everyone’s heads so they can act strategically whenever they face a decision, big or small. A plan on a page or a strategy playbook is rarely remembered, whereas a story is naturally memorable and easily shared.

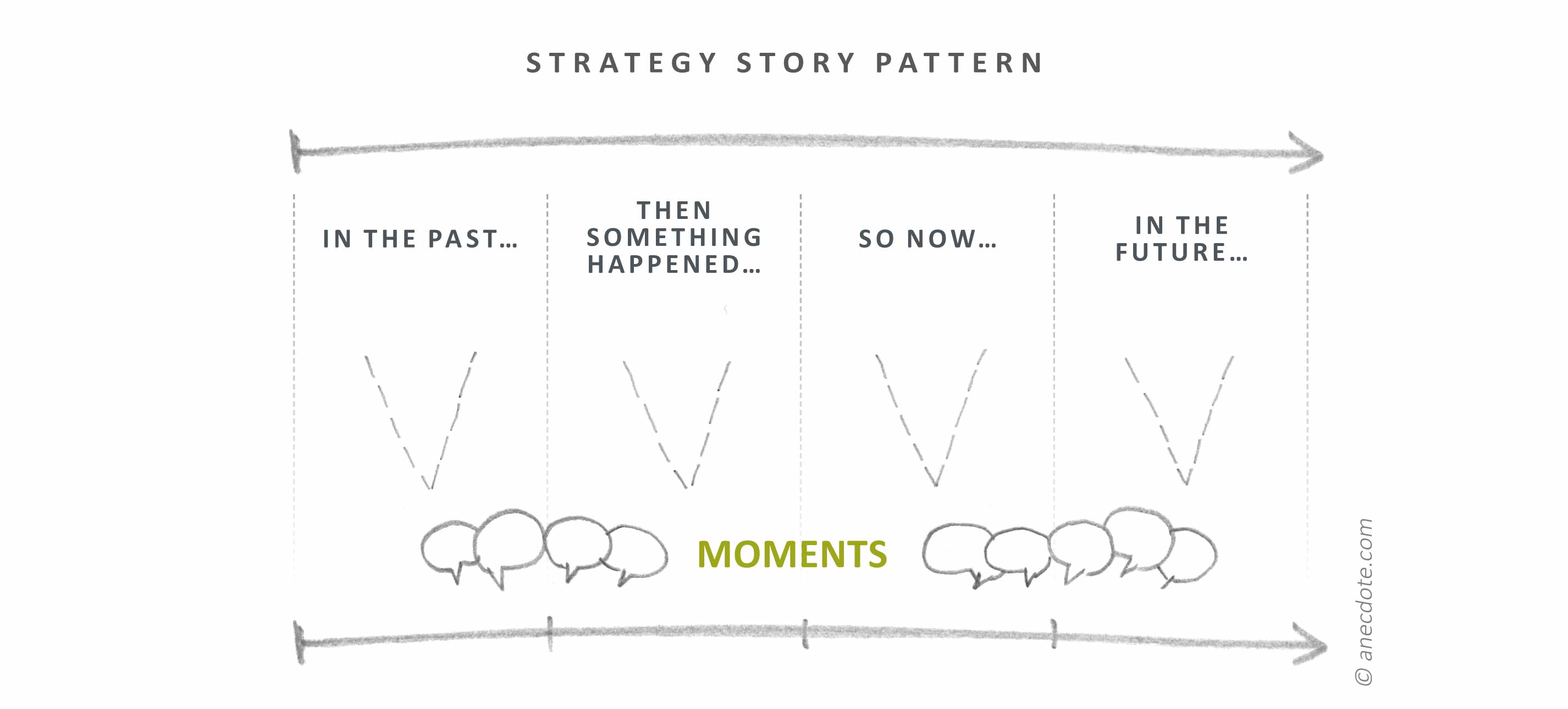

A good strategy is a meaningful explanation of what a company plans to do, its big bets, communicated in a way that helps everyone understand why the company has made its strategic choices. It should also paint a picture of the future that’s compelling, even inspiring. This type of communication is perfectly suited to a strategy story.

The typical solution

Strategy stories are often crafted by the executive team, yet their power comes from engaging a wider group of leaders in the story creation process. The more leaders are involved, the more people who own the strategy story.

Once the strategy story is crafted, leaders need to learn how to tell it off the cuff, without notes, and by adding their own personal anecdotes.

Now that your leaders can tell the strategy story, it’s important to find opportunities to tell it. Asking leaders to weave the story into any pitch for resources or new initiatives ensures the strategy always sets the context for decision-making.

So far we have only discussed top-down initiatives. It’s important to also find stories of the strategy already happening, which illustrates progress.2 We are highly motivated by progress. These stories should be shared widely and talked about, because if you want to change a culture, you need new stories to be told.

2 Amabile, Teresa and Steven Kramer (2011). The Progress Principle: Using Small Wins to Ignite Joy, Engagement, and Creativity at Work. Harvard Business Review Press. https://www.amazon.com.au/Progress-Principle-Ignite-Engagement-Creativity-ebook/dp/B0054KBLBI

Resources

Presentations and keynotes

‘According to most studies, people’s number one fear is public speaking. Number two is death. This means to the average person, if you go to a funeral, you’re better off in the casket than doing the eulogy.’

—Jerry Seinfeld, Comedian

The business problem

Most business presentations are dry and boring, and as a result totally forgettable. The mistaken assumption is that clear points organised in a rational way and spoken out loud or placed into a fancy PowerPoint template can pass as an effective business presentation. Left-brain efficiency may rule the way we operate in business processes, but it shouldn’t rule the way we communicate.

The typical solution

Storytelling is a tool that can overcome this common pitfall. A series of well-placed anecdotes pulls the audience into a journey and turns dry logic into interesting context. It also helps a presenter connect with the audience at a personal level.

Story pulls the audience into a journey

In 2018, while working for Amazon Web Services, we helped an executive—let’s call her Kylie—prepare a presentation for 10,000 people in Las Vegas. Kylie had led a digital transformation in her emerging nation, focused on eight pillars. She now planned to share all eight, in detail. But this would have made for a boring presentation, with no sense of movement. Instead, we found a journey in the way Kylie’s team tackled her nation’s connectivity challenges, which had stunted medical access, education, and growth. This created an urgency to shift her team’s role from being operational to become leaders of the connectivity drive. Her team was cast as the character facing many ups and downs on the journey but eventually triumphing.

Delivering a list of bullets in a rational structure is akin to force-feeding the audience and expecting them to rapidly digest the entire meal. Story, on the other hand, offers more space, whereby the audience can make their own connections, visualisations, and conclusions.

Delivering a list of bullets in a rational structure is akin to force-feeding the audience and expecting them to rapidly digest the entire meal. Story, on the other hand, offers more space, whereby the audience can make their own connections, visualisations, and conclusions.

Story takes the audience on a journey from one state to another, with ups and downs that hold their attention. Contrasting the current state and future potential creates tension. But a good presentation will go further, continuing to raise and collapse audience expectations. This may be through the unfolding journey of a leader, an employee, a customer or a combination of these, but the crucial point is that overcoming hurdles, leading to some kind of transformation, holds our interest.

Story puts dry presentations into compelling context

Presentations are full of assertions and opinions, which may be backed up with facts. Story, however, allows the presenter to wrap facts in context and deliver them with emotion—small anecdotes can have a big impact.

For example, Kylie described how the transformation made her team more strategic. On its own that’s a rather bland assertion, but she tied it to a small anecdote, recounting the first time she was called into a board meeting. The company’s president had relied on Kylie’s IT perspective to make a crucial decision, when before IT barely had a voice. Using this small anecdote, Kylie gave credibility and meaning to her assertion.

You can also use a story structure to make the ‘why’ behind a call to action more compelling. It helps create an imperative to overcome inertia. For example, to explain a restructure you may share the story of sceptical employee who resists change but soon sees their customers leaving in droves. This leads them (and the audience) to not only hear the reasons for the restructure but to feel the urgency for it.

Story makes a presentation personal and relatable

Story gives the audience a feel for what’s at stake. Most presentations remain in organisational or task-driven realms, but story allows the presenter to bring in a more human perspective. As we relate to other people, we’re more likely to care about the outcome than we would for a generic corporation. In fact, the more specific you can get—introducing dialogue, characters, times, and places—the better the story will resonate.

And it’s not only the presenter who uses story. The audience can start to identify their own roles within a narrative or in relation to an anecdote. They can start to see how their work or innovations can advance a story.

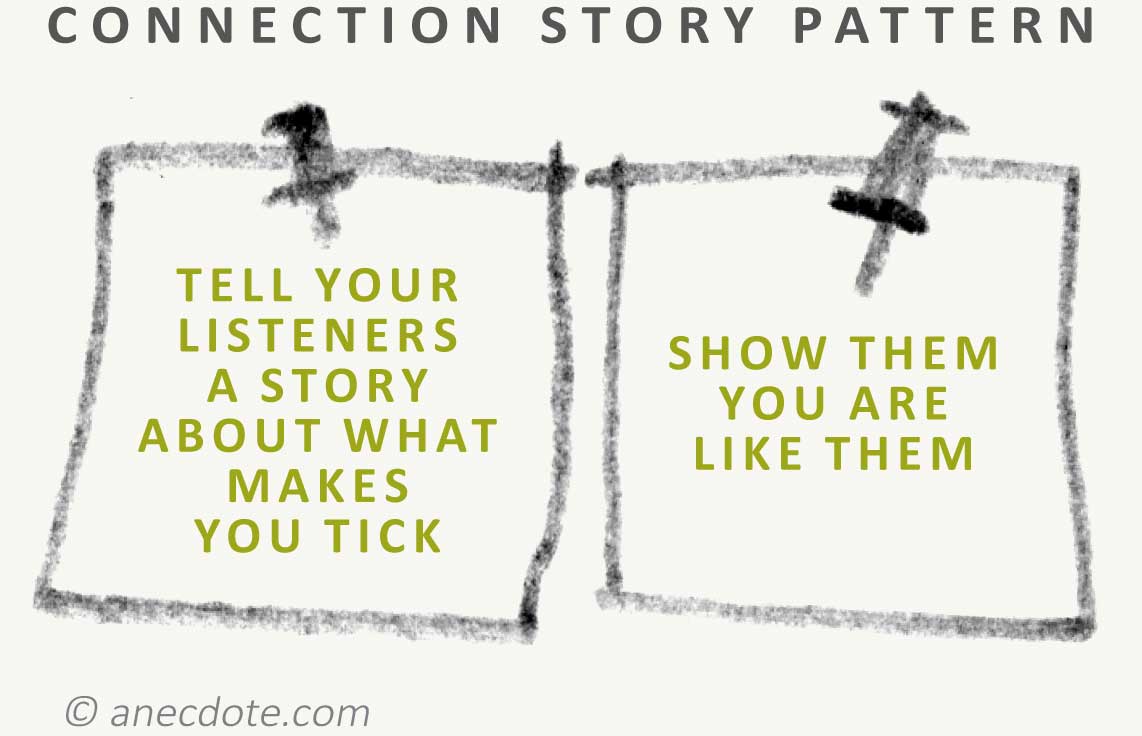

Effective presenters also use story to share why they personally care about something. We call this a connection story. For example, every leader says people are the most important factor in their organisation. That’s a motherhood statement until the speaker provides a specific story showing why they hold that belief or what action they are taking in relation to that assertion. More important than being a dynamic speaker or crafting beautiful slides is the underlying story. Kylie was a very quiet presenter; yet, she was able to hold the attention of a large audience because she had a compelling personal story.

Effective presenters also use story to share why they personally care about something. We call this a connection story. For example, every leader says people are the most important factor in their organisation. That’s a motherhood statement until the speaker provides a specific story showing why they hold that belief or what action they are taking in relation to that assertion. More important than being a dynamic speaker or crafting beautiful slides is the underlying story. Kylie was a very quiet presenter; yet, she was able to hold the attention of a large audience because she had a compelling personal story.

So the next time you have a list of facts or set of initiatives to share with your teams, try and find some stories that gives them flavour and wrap them in tangible or personal examples.

Resources

Data storytelling

‘The ability to take data—to be able to understand it, to process it, to extract value from it, to visualise it, to COMMUNICATE IT—that’s going to be a hugely important skill in the next decades.’

—Dr Hal R. Varian, Google Chief Economist

The business problem

Before 2010, you hardly ever came across the term ‘data storytelling’. Now it’s everywhere. What happened?

The idea of data dashboards was introduced in the 1970s, but they didn’t take off until the 1990s when data warehouses became part of the enterprise technology suite. And with that new pool of management data, leaders wanted ways of seeing what was happening in their business.

There was an information explosion, and dashboards became—and still are—useful for exploring if something interesting was happening in the data. But decision-makers also wanted ways of explaining what was happening and what might happen next. They wanted business insights communicated in a meaningful way, and it would be even better if their data-driven insights inspired action.

About the same time, in the late 1990s, corporate storytelling was emerging. It seemed natural to combine data, visualisations and story to create a new way of communicating data-driven insights.

Analytics teams were the first to learn how to do data storytelling, so they could move beyond mere reporting and churning out standardised information products, and create more value for business leaders. With data storytelling, they could help decision-makers explain what was happening and inspire high-quality decisions.

Unfortunately, the first attempts at data storytelling left out storytelling—they were merely data visualisations. This was a big problem because omitting the explanatory power of story left beautifully presented data inert. Storyless data visualisation didn’t have the desired result of helping decision-makers take action.

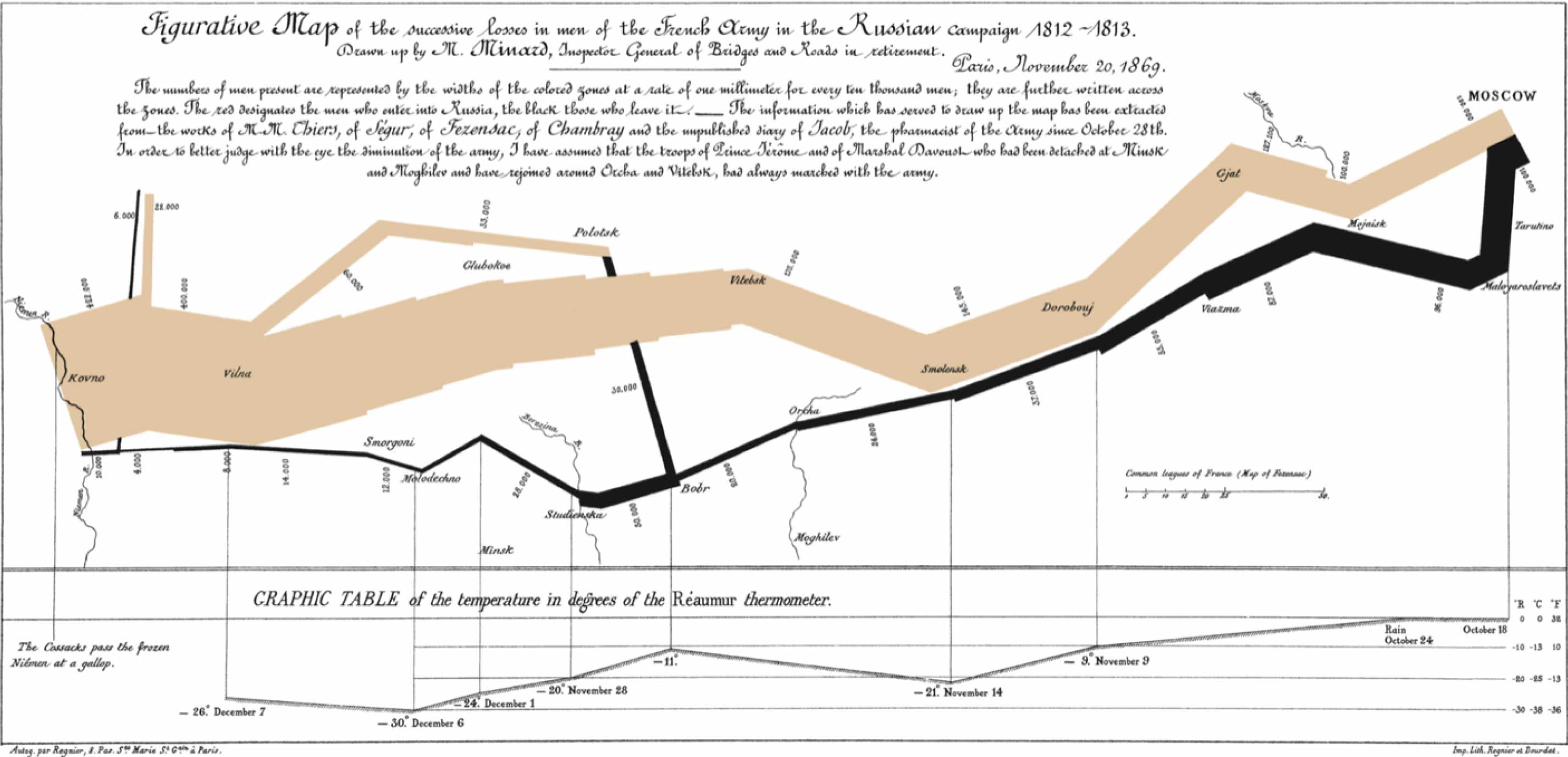

Source: wikipedia.org. One of the earliest examples of great data storytelling is Charles Joseph Minard’s illustration showing the terrible fate of Napoleon’s army march into Moscow.

Thankfully, this problem was rectified among the top practitioners when people understood the difference between a story and a non-story. That said, there are many practitioners who have taken their story lead from Hollywood, referring to three-act structures and the hero’s journey, and comparing data stories to Disney classics. When you are experienced at collecting stories in companies, you understand that the type of story told in business bears little resemblance to Hollywood tales. Instead, they are small anecdotes. A data story should be more like an anecdote than a screenplay.

It wasn’t long before number-savvy leaders wanted to learn data-storytelling techniques. Everyone immersed in an evidence-based culture wanted to move beyond presenting a table of figures and hoping their audience could divine what was going on.

The typical solution

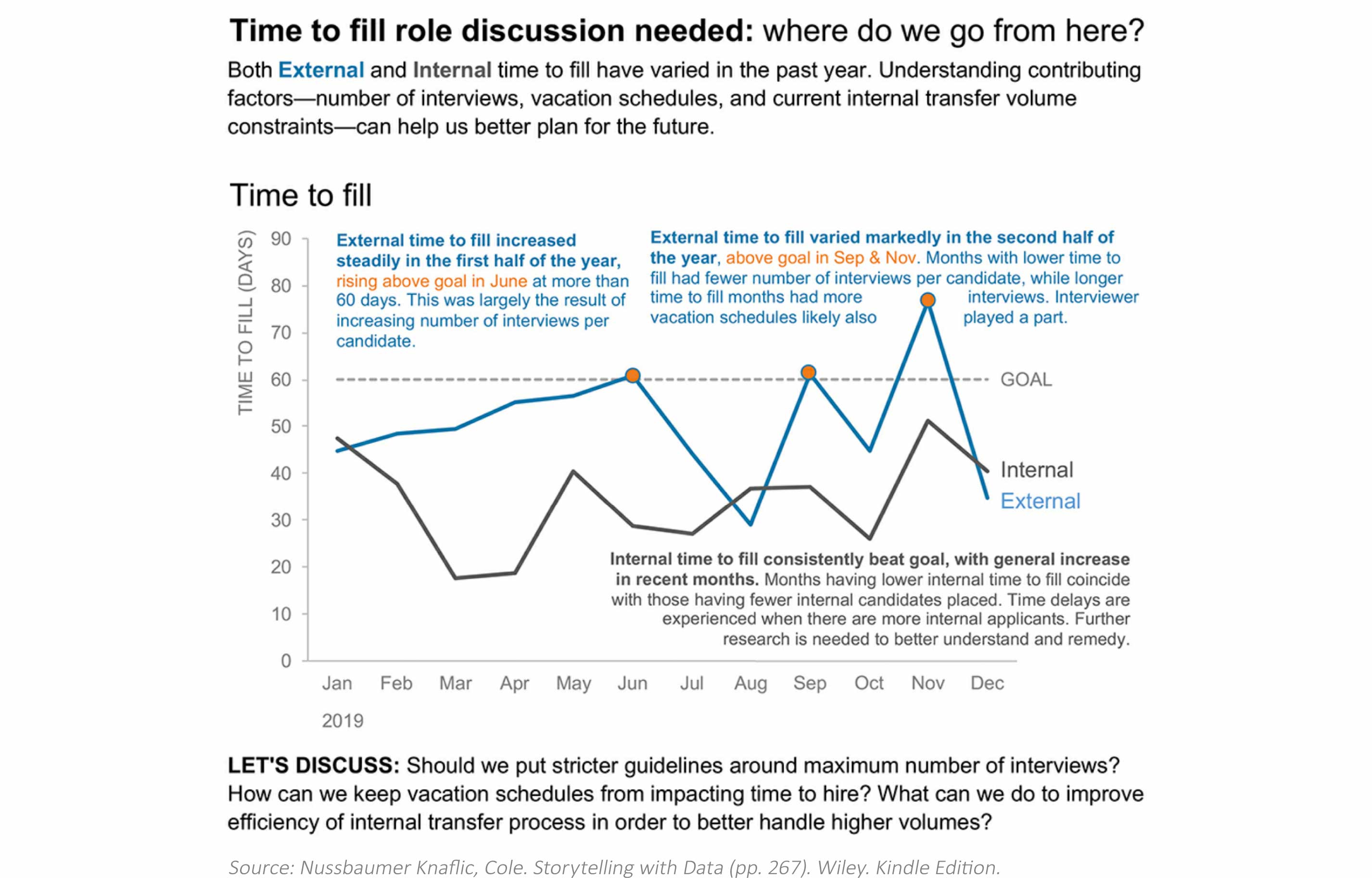

Data storytelling is a skill. As such, the main solution is training. An important starting point for data-storytelling training is finding an insight that you want to communicate. The psychologist Gary Klein said that insight is ‘an unexpected shift to a better story’. So data storytelling is about helping people communicate that better story, and finding insights becomes the starting point.

Once the cohort is comfortable finding insights in their data, it’s necessary to show them how to turn data elements into a data story. Simple story patterns are helpful here. Stepping participants through the process of transforming their data elements into a data story is thrilling. People love before-and-afters. Using data examples from the organisation will show all the complications and nuances that must be tackled by that specific company. Real data makes it real.

The training shouldn’t stop with a couple of workshops, though. Ideally, the participants will partake in a deliberate practice program that encourages them to keep practising, but which also exposes them to more data-storytelling examples. We acquire storytelling over time. That requires people to be immersed in data storytelling. Attending a single workshop is a waste of time.

Resources

Culture change and change management

‘Storytelling reveals meaning without committing the error of defining it.’

—Hannah Arendt, political theorist and philosopher

The business problem

Culture change is not just about storytelling, but you can’t achieve it without using story. Story provides a meaningful anchor to align the different elements of change. Unfortunately, this potential is often overlooked and storytelling is relegated to a subset of communication activities, just one of many boxes to tick in culture-change efforts.

A few years we were working for a US brand agency and asked to use storytelling to help a Bay Area pharmaceutical client shift its culture of drug development. The client wanted to go beyond traditional clinical trials and embrace a new drug-development approach that used real-world data, from actual patient situations. The project lead shared a change-management plan with a strong communications component in Phase 1, around the change story, but only token mentions in the remaining 3 phases. We refused to sign on to do Phase 1 only, arguing that story was critical for all phases. We lost the job. However, a month later people were struggling to see how all the activities came together. We soon got the call up to shape the change story for Phase 1 and the green light to use story throughout the change journey.

The typical solution

Most change stories end their usefulness after the leader’s launch presentation. However, that’s like using a compass at the start of a sea voyage to set the general direction and then never paying attention to it again as you cross the ocean. Story gives meaning and focus to a change. It can also help cascade change throughout the organisation, frame change activities, overcome objections, offer tools to embed change, and offer a meaningful way to track and adapt change efforts.

Story gives meaning and focus to the change

An effective change story explains the ‘why’ and creates urgency for action. It frames the shift from the old way of doing things to the new way. It gives context for the audience to embrace a new role, behaviours, strategy, mindset or customer focus. Importantly, a story does not try to define the entire change in detail. It reveals the contours, then allows each individual to fill in the details. It also cuts through corporate-speak to connect people with the new reality. Story helps cascade a change.

People equipped with basic story skills can share a change across an organisation—by telling stories. Not epic tales, but tangible true daily events. These examples (anecdotes) show culture shifts in action rather than in the abstract. For example, an organisation may aim to shift to become more calculated risk-takers. This can be defined in words, but that does little to make it real for most people. Instead, a simple story can immediately put the value into context—for example, a real decision that an employee faced in a customer scenario. These types of small stories often prompt other stories that help spread the change across teams.

Storytelling can frame all change activities

Storytelling also has a role to play in the execution of hard-edged activities like project management. Activities are often presented as a to-do list, separate from their purpose. By putting them into a change story, people can make a link between what they are doing and why it’s relevant. For example, the pharma company had developed a story around the theme ‘Doing now what patients need next’. This was not just a slogan. It was linked to examples of what that it meant in practice for different functions. ‘Imagine if’ story patterns were then used to share exciting visions of the future that sparked innovation. Training programs, performance management systems and recognition programs were all built around ‘Doing now what patients need next’. In this way, the vital elements of culture change were held together by a common story.

Story can overcome change resistance

A significant challenge to change comes when people resist doing things differently. When a regulator is comfortable with assessing clinical drug trials and is then asked to use non-clinical evidence from real-world experiences, they may understandably have objections. Most change efforts deal with an objection by providing fact-based counterpoints. However, when arguments are pushed at us, we tend to dig in and become even more resistant. Instead, story provides a means of getting people to open up because storytelling is a pull strategy. You create a non-threatening scenario that the listener is able to picture and absorb in their own way and, at the same time, they can pull it in and digest the facts that challenge their way of thinking.

Storytelling helps embed change over the long term

Finally, culture change is an ongoing and evolving process. The situation six months down the track are likely to be different. Rigid change plans are overly optimistic (even ironic) but commonplace. Building in flexibility is essential and can be achieved by using adaptable stories that are refreshed. In order to embed change messages, forward-thinking organisations will also capture and catalogue stories in a story bank. This provides a resource of categorised anecdotes that can be drawn by leaders to illustrate change happening. Progress is motivating. And if the story bank is designed correctly, people will add to it and it grows in value over time.

Resources

Brand communication

‘Your brand is what other people say about you when you’re not in the room.’

—Jeff Bezos, Amazon CEO

The business problem

There is no doubt that strong brands are valuable. They demand higher prices; create better stock prices; are more likely to elicit a purchase, and return purchases; and attract great employees who stay longer. For all that to happen, a business must have a clear picture of who it is, what it stands for, and why it exists. It needs a clear understanding of its brand.

When you hear leaders ask, ‘What’s our story?’, it’s often a sign that the brand is unclear. Of course, it’s never a single story but rather an ecosystem of stories that makes up your brand.

The typical solution

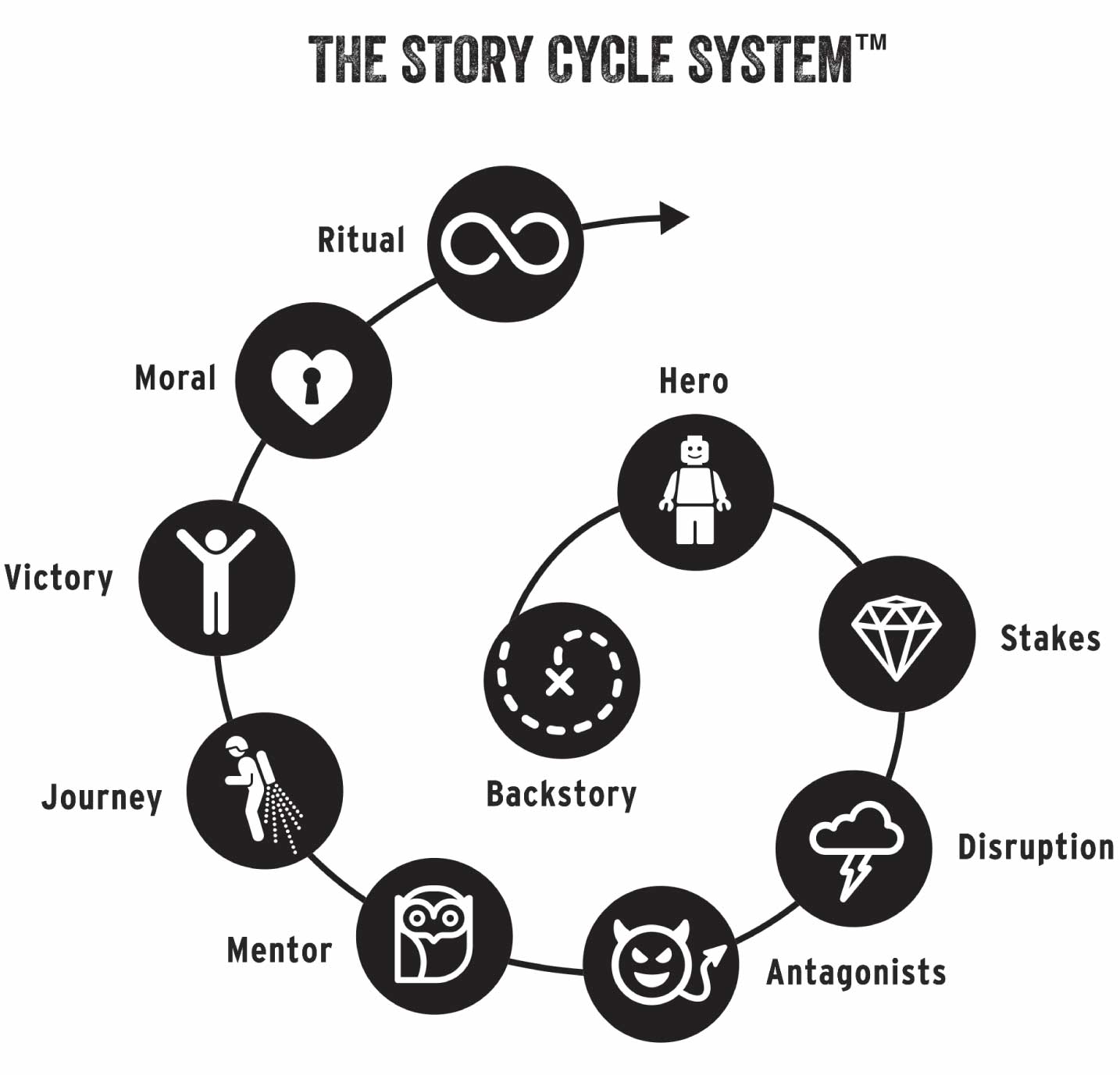

Many brand story specialists will step the leadership and marketing folk through a facilitated process of defining the brand using narrative elements drawn from Jungian psychology, and Hollywood techniques such as archetypes, the hero’s journey and storyboards.

Source: businessofstory.com. Park Howell’s Story Cycle System™ for branding.

(Reproduced with permission.)

Once the big picture is defined, a story approach to brand communication will jump into understanding the customer experience from the point of brand awareness to becoming a customer. Story listening is an important technique here, so a company can hear how customers remember their experiences and then use this feedback to tweak the customer journey.

There are so many places for employees to be on-brand. But instead of teaching employees how to act on-brand, companies like Apple and The Ritz-Carlton create situations where employees can hear stories of when their colleagues have lived the brand.

Apple, for example, runs morning huddles in its retail stores where the manager reviews individuals’ NPS (net promoter score—an indicator of customer service success) from the previous day. If someone gets a high score, the manager asks that person to recount what happened that led to the great NPS. The employee then tells a story about delivering great customer service, while everyone else listens and understands how to do this. The manager congratulates the employee and everyone applauds, reinforcing the behaviour.

Resources

Narrative insight

‘If you listen to enough stories patterns will emerge that were once hidden.’

—Charles Duhigg

The business problem

Late last year, a company approached us to help them with employee engagement. They’d received the results of their biannual engagement survey and, as with previous years, realised that while the data pointed them to strengths and potential weaknesses, it didn’t help them understand what was really going on, or what to do about it. The data might show that 63% of their people agreed or strongly agreed with the statement ‘I am proud to work for this company’, and that this was down 6% from the previous survey. On its own, however, the data won’t help with the questions, ‘What does this mean?’ and ‘What should be done?’.

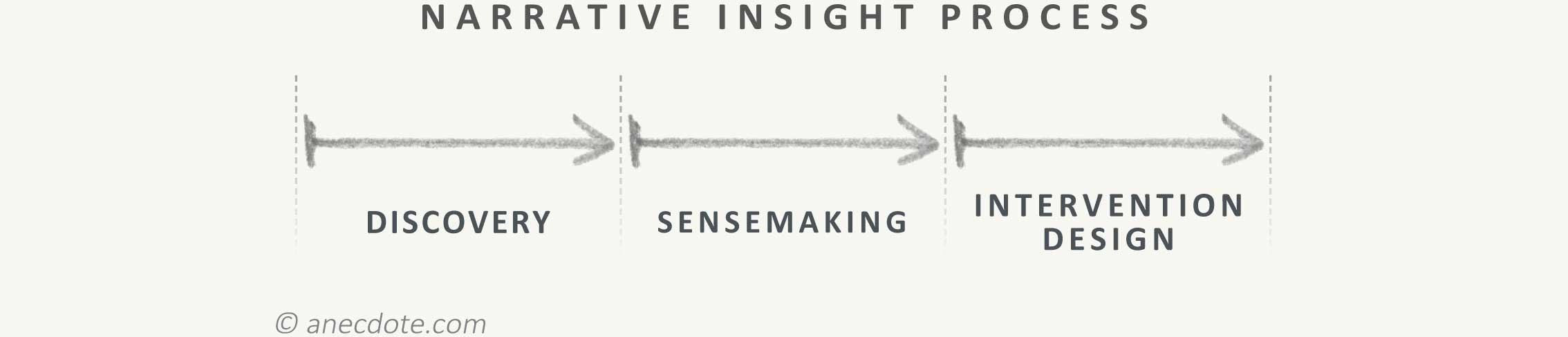

Narrative insight involves collecting real-life experiences (anecdotes) and then helping decision-makers in a company to make sense of the patterns of behaviour demonstrated in the stories. It’s common in this approach to step through three stages: discovery, sensemaking and intervention design. It’s excellent for helping organisations find out what’s really going on in their business, and what actions they can take to reinforce the things that are going well and improve the things that need work.

The survey data is vital ‘targeting information’, but on its own it is insufficient for planning. Rather, exploring employee engagement is a natural marriage of traditional approaches such as surveys and the emerging practice of narrative insight.

The typical solution

Employee engagement surveys often focus on areas such as whether people say positive or negative things about the organisation, their intent to stay with the company, and whether they are motivated to strive to do the best they can for the company. In preparation for the narrative project, the survey data is examined to identify the themes to be explored, the geographic or structural areas to focus on, and the people to involve in the project. Stakeholders are also asked for their views on the survey results and the things that are of most concern or most surprising to them.

Anecdote circles are used during the ‘discovery phase’ of these projects to collect a large number of examples (anecdotes) of how people at all levels of the organisation experience issues on a day-to-day basis. The anecdote circles are an intervention in themselves, as they get groups of people to share their experiences, people value the opportunity to be listened to, and participants learn from each other about how things get done.

During a recent anecdote circle, a participant related how he received a call early one morning from his manager asking if he’d heard about the severe storm warning for his area (he hadn’t). The manager was worried about him driving to work in the storm and requested that he work from home that day. The guy telling the story was really impressed by the phone call. This was a great example of how small actions can really build employee engagement.

In the sensemaking phase, a significant and diverse group of influencers are exposed to a cross-section of the collected anecdotes and are facilitated to talk with each other to identify issues and themes regarding the current situation. The idea of sensemaking is to develop a rich, common understanding among the influencers of the situation and its history. Exposure to the anecdotes gives participants insights into what really goes on in the organisation. This can be quite confronting at times, but nonetheless, sensemaking is a vital step—the individual and collective understanding it provides is the springboard for deciding what action to take. The sensemaking workshop takes between four hours and a full day, and one of its valuable side effects is that individuals will often change their behaviour (deliberately or subconsciously) back in the workplace because of the new understanding they’ve developed. This is an important step, as one of the necessary actions to improve employee engagement is to ‘stop doing things that piss employees off’.

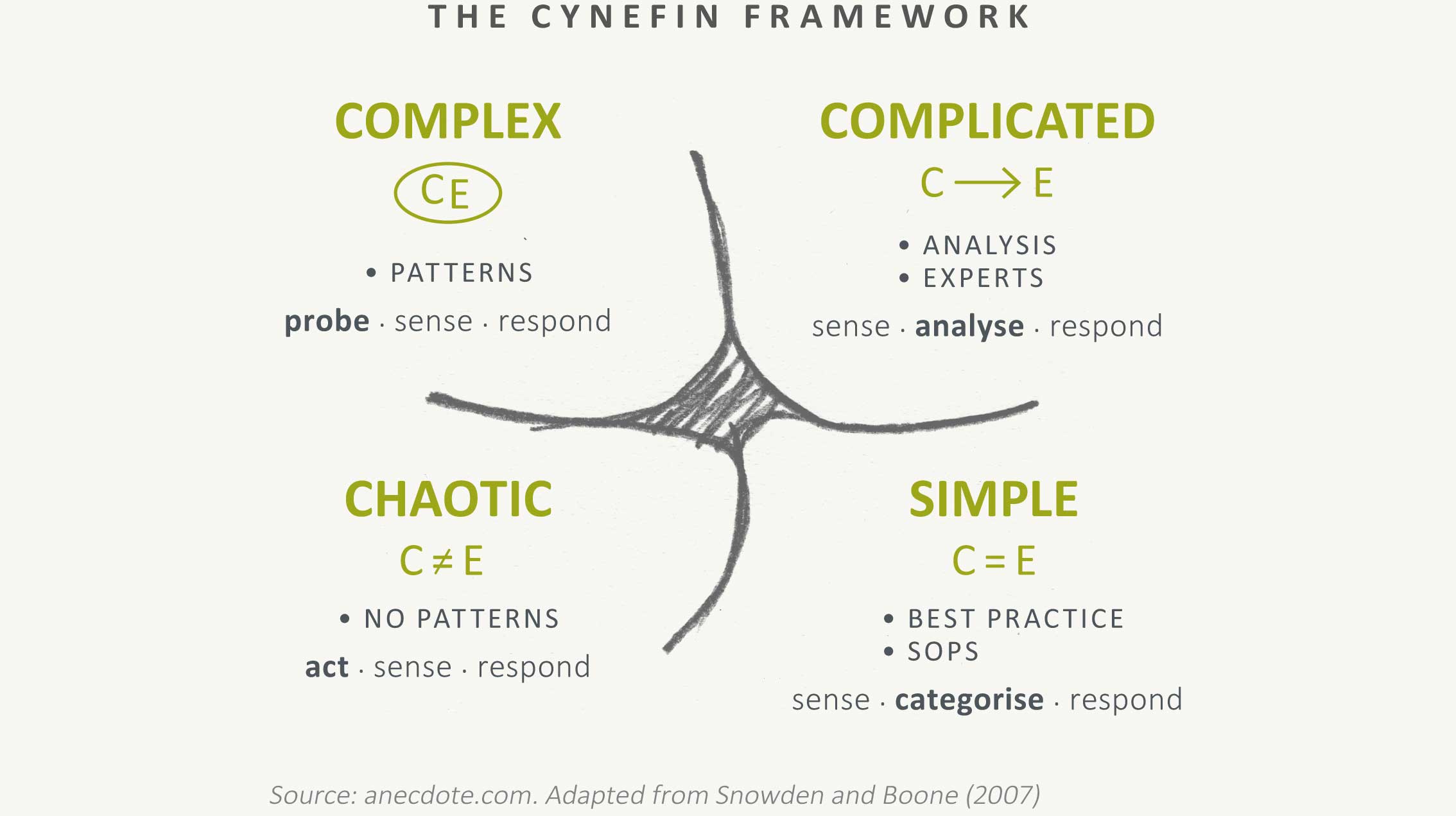

Complex problems cannot be ‘solved’ in any traditional sense of the word. This is something we learned many years ago working with the Cynefin Framework. The way to make progress is to try things and see what happens. Using the deep understanding developed during the sensemaking phase, we involve influencers in identifying the actions that can be taken to move the situation in a desirable direction. Our approach to this stage (in initiative design) is strongly influenced by the characteristics of complex problems, meaning we encourage the organisation to identify lots of small-scale actions that can be taken at an individual or team level—based on the knowledge that with complex problems, small things can make a big difference. We also encourage a ‘continual improvement process’ that aims to get these changes embedded in the fabric of the organisation.

The final stage is to monitor what happens as a result of the actions taken—reinforcing the patterns that are beneficial and disrupting the ones that aren’t. This is done through the embedding process developed during sensemaking and by using techniques such as Most Significant Change (an evaluation technique discussed later in this article). A planned monitoring regime is important too, as it helps detect changes, and it also works as an incentive to take the actions identified during the intervention design.

Resources

Job applications and interviews

‘Whenever you are asked if you can do a job, tell ‘em, “Certainly I can!” Then get busy and find out how to do it.’

—Theodore Roosevelt

The business problem

For many years, the standard job-interview question went something like this: ‘What are the important strengths you would bring to this role?’ This approach often made it difficult to differentiate between candidates. Every candidate would claim to be ‘a good communicator’, a good team player, have excellent attention to detail, etc. etc. In most cases, the selection decision was made on the strength of the résumé—on the strength of the candidates’ claimed credentials.

All too often, this approach ended in poor selection decisions, poor job performance, and all the associated problems and costs this brings. The person claiming to be a team player turned out to be a ‘ladder-climber’, and the ‘good communicator’ just barked orders at their teammates. You would end up selecting people who were good at writing applications and good at looking good in an interview rather than those with ‘the right stuff’ for the job. The application and interview process didn’t reveal the candidates’ true character.

Recognising the limitations of this approach, a number of years ago a movement began towards ‘behavioural interviewing’. This approach focuses on identifying the candidates’ ‘key strengths’ and then asking them to give examples that illustrate these strengths (or values, achievements, weaknesses etc.) and reveal the sort of person they really are (their character).

Regardless of the approach, candidates achieved more interview success when they were able to give engaging, credible and impactful examples that illustrated their abilities and demonstrated their character.

Most advice about succeeding in job interviews goes like this: ‘To prepare, start by thinking of 3–5 strong, relevant adjectives that describe you and your values. Tell the interviewer what they are, then give real examples of how you embody the adjectives.’ At face value, this is sound advice. The big problem is knowing how to identify, practise and effectively deliver these ‘real examples’.

This is where corporate storytelling helps.

The typical solution

The following sections outline some of the main ways in which story can assist during the interview process.

Build connection and rapport

A friend had returned to work after a six-week holiday in Spain. She was happy to be back but faced nearly 100 applications for several vacant positions. Her job was to short-list the candidates for interview, but it was a laborious task as she found it difficult to differentiate between the applications. ‘But there is at least one applicant who will get an interview,’ she said. ‘On their application they mention they are from Cordoba in Spain. I loved Cordoba when we visited there on holiday a few weeks ago.’ This tiny connection made the application stand out and the candidate went on to win the position (not just because she was from Cordoba).

In this case, the applicant unknowingly established a connection that made a huge difference. They got lucky. But the difference it makes when you can establish a connection is not luck—it’s just how humans are. So don’t leave it to good fortune. Your first task, both in applications and interviews, is to establish a rapport and connection with the reader/interviewers. Sharing a relevant experience, a personal story, is a great way to quickly establish this rapport.

Demonstrate your skills and attributes

Most job applications will have selection criteria or lists of skills and attributes the employer is looking for—things like adaptability, customer focus, teamwork, etc. Applicants should identify the most important criteria and then find some examples (stories) that illustrate them. To do this, applicants need to ask themselves questions like this:

- Adaptability—Think back to a time when you were asked to do something you had never done before. How did you react? What did you learn? How did you feel during the process?

- Collaboration—What has been your favourite experience working with a team? What happened? What was your contribution? What was achieved?

- Leadership—When have you learned an important lesson about leadership? What happened?

- Values—Think about a time when one of your values was tested and you had to decide between doing the easy thing and doing the right thing. What happened?

Practise describing these experiences out loud to a friend or colleague. Ask for their feedback. What did they like? What did they infer about your character? How can the story be even better? You’ll need to say the story out loud 3–5 times to refine it and reduce it down to about 60–90 seconds’ duration. Following these steps will help your story have impact and be as short as possible.

Interview the interviewers

A job interview is a two-way street. Just as the potential employer is assessing you for the role, applicants are assessing the company for their suitability as an employer. One of the best ways to get insight into what it’s like working in the organisation is to hear examples (stories) of how things really work there. Questions about values in action, what success looks like, etc. can be revealing.

Asking thoughtful and insightful questions increases an applicant’s chances of success and it gives the applicant more insight into whether this is a place they’d like to work in.

Resources

Customer experience and customer service

‘Make the customer the hero of your story.’

—Ann Handley, author and customer experience expert

The business problem

Customer experience (CX) specialists map and optimise the customer’s journey from awareness through consideration, purchase, service and loyalty expansion. The challenge is to correctly analyse each customer touchpoint and design the best experience.

The typical solution

A major manufacturer and distributor of door locks identified installation as a problematic experience for their customers and service technicians. After a CX analysis, the company invested in a 3D graphical assembly app for their product suite. A QR code on the product packaging launched the app and each assembly step was shown in an exploded 3D diagram. The new app instantly reduced the number of support calls and product returns, and it increased customer satisfaction. The company was also able to reduce the training time for its technicians and the installation time for each job.

The CX designer’s challenge is to correctly diagnose the existing client journey, identify the areas for improvement, and design a better experience. Soliciting customer stories rather than customer opinions is a crucial tool in doing all this. The question ‘How do you rate the assembly instructions?’ may elicit a short opinion (‘They were terrible’), but the story-seeking question ‘What happened when you assembled it?’ or ‘What went wrong?’ yields rich data and insights into the customer’s unexpressed needs and concerns.

The most complex part of CX design is managing the interactions between people. Ensuring your customer-facing employees say and do the right thing is difficult to manage with processes and procedures, but stories that exemplify good service behaviour can have a magical effect. Top performers in the hospitality industry have long recognised the power of customer-service stories to inspire and teach their people.

In 2012, Chris Hurn, the founder of Fountainhead Capital, stayed with his family at the Ritz-Carlton resort at Amelia Island in Florida. On returning home, Chris realised his son’s toy giraffe ‘Joshie’ had been left behind. To save his son distress, Chris explained to him that Joshie was staying on a few extra days at the resort for some additional relaxation. Chris mentioned his white lie to the resort’s lost-property staff, and when Joshie arrived home he was accompanied by a photo album containing snaps of the fun he’d had on his own at the resort. The lost-property staff even included a photo ID security badge for Joshie.

This is both a ‘How to behave’ story for the service team and a marketer’s dream story!

However, it’s easy to send mixed messages when you want to empower your staff to do the right thing. In the early days of the IT company Hewlett-Packard (now HP), co-founder Bill Hewlett came in to work on a weekend and found the equipment storeroom locked. He smashed the door to pieces with a fire axe and left a note on the wrecked door, insisting it never be locked again because HP trusts its people.

A story like this that shows just how much the leader cares about trusting everyone to access the supplies they need. The dramatic method of opening the storeroom illustrates that. How a leader behaves and how people are expected to behave is worth more than any number of corporate values statements.

Companies invest in storytelling training for CX and customer service leaders for good reason. The best-performing customer service teams incorporate storytelling into their regular meetings.

Resources

Leadership development

‘The greatest challenge in leadership is to change oneself.’

—Nelson Mandela, one-time South African president

Nick was standing in front of a wall of stories. Each A4 sheet of paper sported a single anonymous anecdote illustrating either a good or bad management behaviour, collected from Nick’s company. One story had captured Nick’s attention: ‘In my performance review this morning my manager was on the phone twice. All he has to do is to see a pair of shoes appear outside his door and he’s off to see them and talk to them. It makes you feel very unimportant.’

Nick really took exception to this manager’s behaviour: ‘I can’t believe this guy. Imagine answering the phone during a performance review. Unbelievable—he even stepped out of his office to chat with someone who was just passing by.’

His complaints caused others in the workshop to wander over to see what was going on. As Nick was spluttering his displeasure, Paul, one of his direct reports, jumped in: ‘That was my anecdote Nick, and it was about you.’

Nick’s face turned red and before he could say anything, another colleague added: ‘It totally nails you Nick. It’s spot on. You do it all the time.’

By now, everyone in the workshop was watching. It seemed the next few seconds would reveal Nick’s true character. Nick’s face was ashen as he looked around the room. He gathered himself and then apologised to his colleagues, adding: ‘I can’t promise you it won’t happen again—I wasn’t even aware I did this. But I can promise you that I’m going to make every effort to change my behaviour.’

And to Nick’s credit, he did. At the time of the workshop, Nick was the head of sales and marketing at the company. He’s now the CEO.

The business problem

If there was a universal exam that tested for leadership knowledge, nearly every leader who took the exam would get a pretty good score. Yet people in organisations are more disengaged than ever before, leader communication is often the biggest area of complaint in staff surveys, change programs rarely achieve their objectives, and strategies are rarely understood either by leaders or those on the front line. Lots of money is spent on leadership development but the return is often low.

The biggest problem isn’t leadership knowledge, it’s leadership behaviour. Most leaders return from a development opportunity with new knowledge, only to face the reality of their inbox, priority tasks, staff issues, etc. They quickly forget the theory as they are immersed in the existing culture and the demands of their jobs—their ingrained behaviours kick in and little of substance changes.

The typical solution

Applying corporate storytelling concepts to this challenge provides new opportunities. The neurologist Donald Calne once said, ‘The difference between reason and emotion is that reason leads to conclusions and emotion leads to action.’ Because stories are vehicles for conveying both meaning and emotion, they are effective at changing behaviour.

By collecting stories from employees, we can compile a ‘user guide’ for effective leadership behaviour. Leaders recognise their own behaviour in the stories and become more self-aware, and self-awareness is a precondition for change. We had one manager say to us, ‘This story is just like me and I’m not proud of it.’

Applying corporate storytelling concepts to the leadership development challenge starts by collecting the experiences of employees at all levels in an organisation. Anecdote circles (described in the ‘Narrative insight’ section of this article) are used to collect several hundred stories—both positive and negative—using questions like ‘Think back over the past 12 months. What have been the highlights and lowlights—the times when you’ve gone home and told everyone you love working here, and the times where you’ve gone home and told your partner you can’t stand working here any longer. What happened?’

The workshop experience commences by immersing participants in the real-life experiences of their people. When leaders hear those stories—in the exact words of employees—they are affected at a much deeper level than they are by facts, theories or assertions. Most importantly, leaders understand intuitively what employees are experiencing, and this emotion drives real change. This is exactly what happened for Nick in the example above. One of the simplest actions leaders can take to improve engagement and performance is to identify the things they are doing that reduce engagement… and stop doing them.

One of the recurring pieces of feedback from leaders participating in these programs is the large gap between leader perceptions of their performance and the perceptions of employees’.

Imagine if we had conducted the leadership development program by listing the behaviours a good leader displays and then tried to persuade the participants with theory, logic and reasoning. Change would’ve been unlikely. But, just as was the case with Nick, participating leaders worked things out for themselves and inspired themselves to change.

Here is what one leader said about this approach: “We walked in, and around that room were stories from our people. It was not about another place. It was about what our people saw in our leadership. Forget theory, this is what people are telling you. It was by far one of the most compelling, confronting and valuable insights we’ve experienced.”

Resources

Values communication

‘It’s not hard to make decisions when you know what your values are.’

—Roy Disney, co-founder of The Walt Disney Company

The business problem

In early 2007, I [Mark Schenk] facilitated a pilot of a leadership development program. Part of the program focused on the organisation’s values… The 15 executives had a lengthy and passionate discussion about the critical role that values play in their organisation and how they help guide behaviour. I decided to go off-script and asked all of them to list the five company values on a piece of paper. I collected the papers and tallied the responses. None of them had correctly listed all five. One person got four right. Most got two or three. Five of the executives got zero out of five. Not surprisingly, the participating executives were highly embarrassed.

In the example above, it’s evident that values were an interesting theoretical construct, but that they played a minimal role in influencing behaviour in the organisation. It’s almost as if simply having values was thought to be enough, much like hanging a talisman on a door to ward off evil spirits.

One of the challenges with values is that they are often abstract—they are hard to explain and difficult to remember. Lists of one- or two-word values—things like integrity, respect, customer focus, innovation—simply don’t cut the mustard. Even if you have a few paragraphs describing each value, this does little to help.

The real challenge is bringing these values to life so that people really know what they mean and care about them. This is an important area where corporate storytelling can help.

The typical solution

In 2016, a major bank asked us to collect stories to help its managers understand the values of the business. The bank had connected its values to its performance management system and wanted to rate employees on how well they were living them. But both employees and managers didn’t really know what to say about the values in the performance reviews because they were unsure of what they actually looked like in action.

One of the anecdotes we collected was about a young lawyer who’d just started with the bank and was asked to provide a series of legal documents to an internal client. After he’d finished the work and sent it off, he realised he’d made a mistake. It wasn’t a huge mistake, and chances were nobody would notice it, so at first he thought he’d let it slide. But then he pulled himself up and thought, ‘Is this the way I want to start my career as a lawyer?’ He promptly called his client and told them what had happened. His client praised him for his honesty, while he fixed his mistake and felt good about fessing up.

For the bank, this was one small illustration of what integrity could look like. It also said something about what should happen when a mistake was found.

However, one example is not enough. Managers and employees need a richer picture of their values, and this comes from hearing a range of different stories that show a value in action from different perspectives. In fact, you need to create a systematic way to not only share these stories across the company but help people talk about what the stories actually mean to them. It’s only through this discussion that employees make sense of their values.

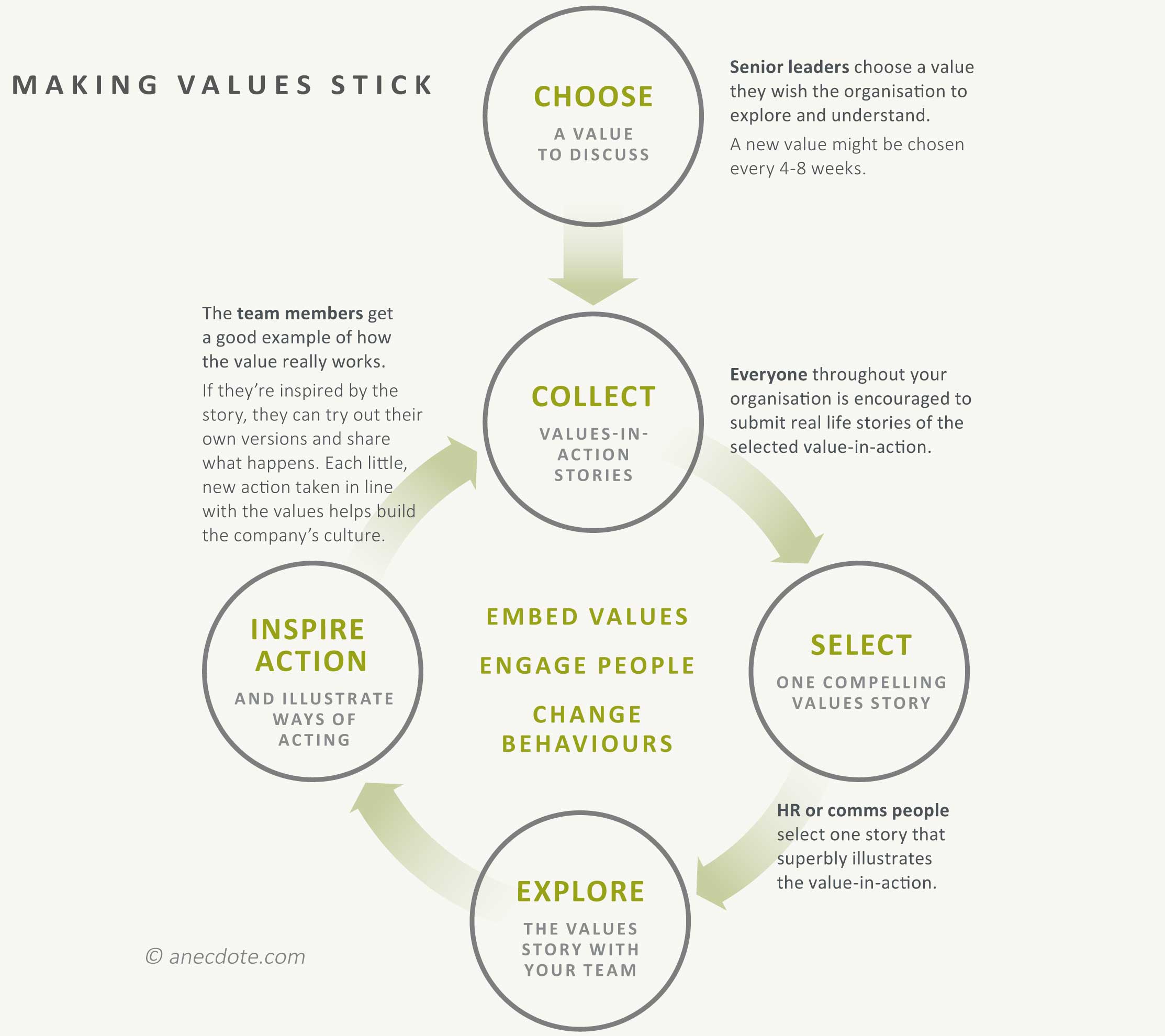

One of the best ways of embedding and constantly reinforcing values is to use a structured story sharing process. The process described below is a generic one that can be adapted for different contexts.

Step 1: Choose a value to focus on. Senior leaders choose a value they want the organisation to explore and understand. A new value might be chosen every 4–8 weeks.

Step 2: Collect stories of the value in action. Everyone throughout the organisation is encouraged to submit real-life stories about the selected value in action.

Step 3: Select a compelling example. The HR or comms team selects one story that superbly illustrates the value in action. This story is distributed throughout the organisation.

Step 4: Explore the values story at the team level. The team leader shares the story with their team and leads them in a conversation, facilitating a deeper understanding of what the value means. The team leader asks questions like, ‘Have we seen examples like this in our area?’ and ‘How can we do things like this in our area?’

Step 5: Inspire action and illustrate ways of acting. The team members get a good example of how the value really works. If they’re inspired by the story, they can try out their own versions and share what happens. Each new action taken in line with the values helps build the company’s culture.

Imagine if your entire organisation is discussing the same story at the same time, say every fortnight or each month. Imagine the gradual but robust understanding everyone would develop of what the values mean. And by telling their own stories (because hearing a story invariably prompts other stories to be told), they will, over time, begin to really own these values. The values will no longer be a set of abstract ideas handed down by the head office.

Resources

Innovation

‘The enterprise that does not innovate ages and declines. And in a period of rapid change such as the present, the decline will be fast.’

—Peter Drucker, author and management consultant

The business problem

As Drucker said, innovation is essential for enterprises, yet most find innovation elusive, and often they outsource the function to their acquisitions and mergers department. There are two fundamental problems here: discovering the innovations and selling the innovations.

Discovering innovations

There is only one way to discover new knowledge, which is to guess at it and then check to see if it works. But the first problem is that with guessing, you are often wrong, and in most organisations, being wrong is not the way to get ahead. So the first issue for innovation leadership is to allow innovators to make mistakes.

The second problem is that the check is often criticism applied too early, before the innovation has been properly developed and had a chance to shine. Most businesses operate by applying and streamlining existing knowledge, and the critical thinking that is essential for managing existing processes kills innovation. Innovation requires a different culture from mainstream enterprise culture—it needs a culture where mistakes and missteps are celebrated, and trials and tests are given enough time to prove their worth.

Since 2000, Google, one of the world’s most innovative companies, has famously allowed its staff to spend 20% of their work time one private side projects. That idea is a modification of the 15% free time policy established by 3M after World War II. Google Maps, Twitter, Google News, Gmail and AdSense are just some of the Google side projects that became major innovations.

Cynics who claim that fewer than 10% of Googlers take up the offer, or Google insiders who complain that it’s more like 120% of employees’ time, miss the most brilliant aspect of this policy. If the nominal 20% is truly your own time, then you can make mistakes. The policy is a licence to freely experiment.

Stories that explain why a change is necessary, and stories of staff that epitomise the innovative behaviours, can drive the change. This is elaborated on in the ‘Culture change and change management’ section of this article.

Commercialising innovations

Invention is merely the first challenge for innovation, which can be defined as a good idea executed well. Taking an innovation to market is often the most difficult part of the endeavour. The world of business is littered with examples of innovations that foundered ‘before their time’.

The seller’s problem with innovation is the lack of a success story. Without a success story—something that explains why the innovation was needed—the new product looks risky and unproven. New business developers must rely on clarity stories to explain change, and on insight stories to teach the buyer how the innovation was discovered. Some might even trigger a compelling story, as with the following example.

In 1982, Barry Marshall, a registrar at Royal Perth Hospital, teamed up with pathologist Robin Warren to study stomach bacteria. Together, they developed a hypothesis that a particular bacterium (H. pylori) was the cause of stomach ulcers and gastric cancer. At the time, it was thought that stomach ulcers were caused by stress and that bacteria could not survive in stomach acid. Marshall and Warren’s hypothesis was ridiculed by the scientific and medical establishment.

After failing to cultivate the bacteria in pigs, Marshall gave himself a baseline endoscopy and drank cultured H. pylori extracted from an infected patient. When he developed ulcers, he treated himself with a targeted antibiotic. The results and publicity from this stunt swayed the establishment and finally antibiotics were accepted as a cure for stomach ulcers. In 2005, Marshall and Warren were awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine in recognition of their discovery.3

The typical solution

Story coaching to help entrepreneurs pitch new ideas is usually purchased as a block of individual lessons and may include video sessions and the creation of pitch videos.

New product marketers and business development staff benefit from storytelling training and coaching to collect clarity (‘Why change?’) stories, insight stories and product stories. A modified version of sales storytelling programs can generate these stories if the right combination of researchers, product developers, marketers and business developers can be brought together.

Leadership story training arms leaders with the stories they need to inspire change and instil the necessary risk-taking and persistence behaviours in their innovation teams.

Most importantly innovators, and those championing innovations, should understand the types of stories that help and hinder new ways of working.

We think there are at least eight story techniques that foster innovation in any company.

3 Wikipedia (2020). ‘Barry Marshall.’ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barry_Marshall; Wikipedia (2020). ‘Robin Warren.’ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robin_Warren

Resources

Evaluation

‘Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.’

—William Bruce Cameron, author and columnist

The business problem

Decision-makers are under increasing pressure to justify their decisions and then account for their success (or otherwise) to a variety of stakeholders. Evidence-based management is further increasing this pressure. While we know that intuition plays a significant role in decision-making,4 big decisions (‘Will we merge and how?’; ‘How will we change our culture?’) require thoughtful deliberation as well as experimentation. A conundrum emerges, however, when dealing with programs designed to change behaviours: how do we know that the program of activities is responsible for the change?

Initiatives designed to change behaviour are notoriously difficult to assess using traditional techniques. Let’s take as an example a learning initiative called After Action Reviews (AAR), an intervention designed to create knowledge and new behaviours through personal and group reflection.

A group is facilitated to discuss the answers to three questions relating to a current or recently completed project: ‘What was supposed to happen?’, ‘What happened?’ and ‘What accounts for the difference?’. Once a program of after-action reviews is in place, is it the AARs or something else creating new knowledge? This knowledge, the argument goes, should create new behaviours. But is it the knowledge gained from the AARs or something else that does this? Finally, these new behaviours should impact organisational outcomes. But again, are the new behaviours creating the impact or is it something else? There are too many causal links in this complex system to know for sure.

Assessing hard facts alone is insufficient to help stakeholders appreciate the impact of a program designed to change behaviours. Qualitative perspectives are essential. The need to balance out hard facts is heightened by the increasing number and variety of stakeholders involved, each one having their own criteria and needs. A new method of evaluation has been needed.

The typical solution

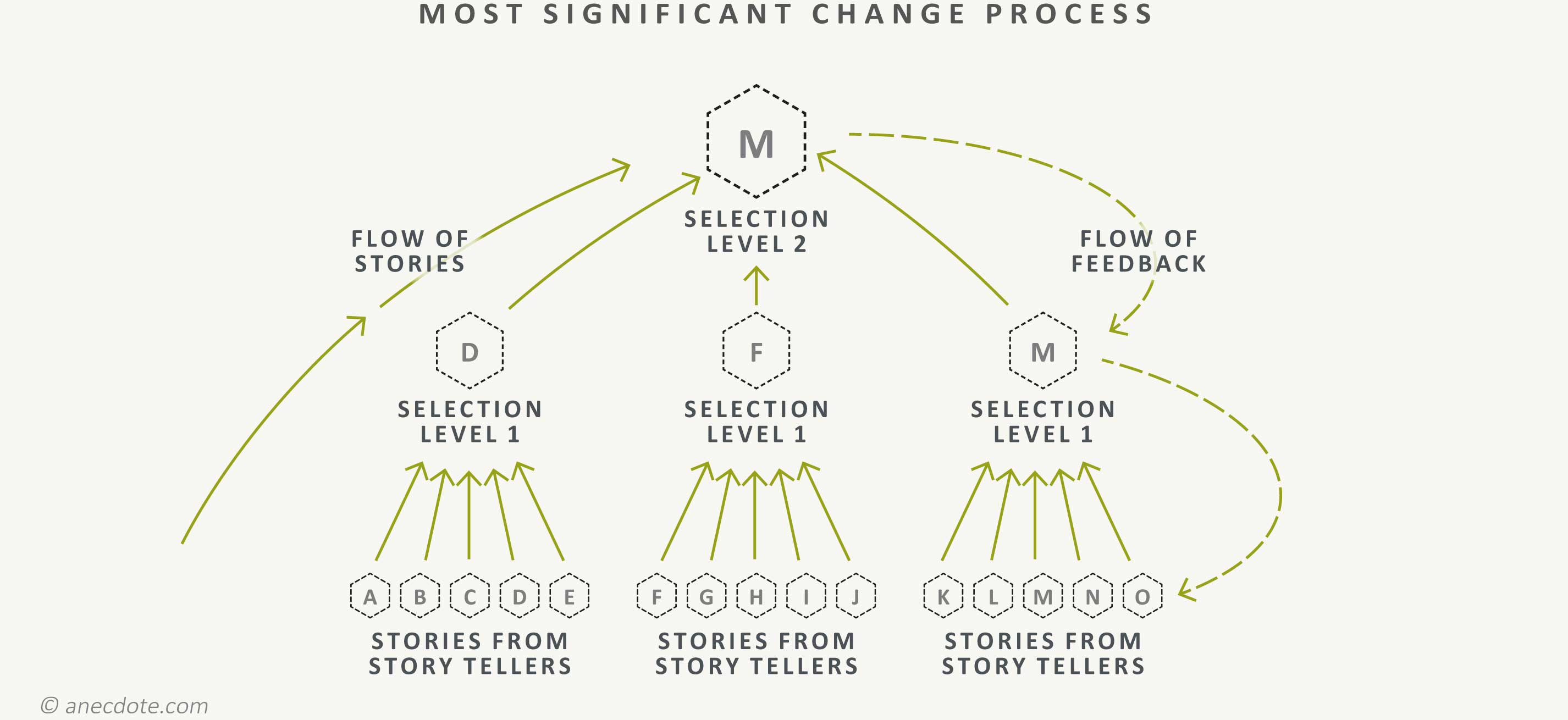

Most Significant Change (MSC) is a simple process for helping senior decision-makers develop a gut feel for what an initiative has achieved. It’s not a replacement for gathering and analysing the numbers. Rather, it’s a supplemental evaluation that helps to systematically develop decision-makers’ intuitive knowledge. And research shows that many of the decisions we make are based on our judgements and intuition, so it’s a part of our knowledge we mustn’t ignore.

MSC can be done in four steps.

Step 1: Collect stories of significant change

The process starts by asking two simple questions of the people affected by the initiative of interest:

- What is the most significant change that has happened since the initiative started? This typically results in stories.

- Why is this change significant to you?

Step 2: Identify and assemble the decision-makers who need to know what really happened as a result of the initiative

This step, which is crucial to the success of the evaluation, consists of the evaluation designers asking the question, ‘Who needs to know, in their gut, the impact this initiative is having?’ These decision-makers could be at any level in the organisation, in any location. The evaluation designer organises the decision-makers into groups of 6-8 people and arranges for these groups to meet for 90 minutes or so to consider the significant change stories collected in Step 1.

Step 3: Select the Most Significant Change story

When you have your decision-makers in a room, the facilitator guides the group in a discussion of 4-6 of the stories that were selected. In fact, we encourage the group to read each story, then argue why they think a particular story is the most significant. This discussion helps embed the stories in the minds of the participants while raising issues of strategies and implementation. The participants experience a lively debate and get to know one another and the issues affecting people in the field. Most importantly, they develop an intuitive understanding of the impact the initiative is having.

At the end of the session, the group agrees on an MSC story and describes why they selected it. They also identify the actions they will take to reinforce the good things that are happening and disrupt the undesirable outcomes. The result is communicated to the original storytellers. The MSC story from each group is then made available to the next level in the organisation, such as an executive group, which repeats the process with the subset of stories.

Step 4: Make the stories and what was selected available

The evaluation concludes with the collation of all the stories and the creation of a document that details which stories were selected and why. Invariably, lessons are learned during the process and these ideas can then be fed into a continuous improvement process.

The selection process is frequently scheduled to occur on a regular cycle. Organisations that use MSC often select a period between selections of 3–6 months to evaluate ongoing change.

4 Klein, Gary (2003). Intuition at Work. Currency Doubleday. https://www.amazon.com.au/Intuition-Work-Developing-Instincts-Better/dp/0385502885

Resources

Conclusion

Businesses don’t invest in story capabilities as an end in itself. Instead, effective business story techniques tackle business problems. The topics we explored above are just the start. Stories are being used in software development, executive coaching, therapy, and every type of learning effort, let alone what’s happening in the entertainment business. We must, however, never forget that we don’t get any of the marvellous benefits of storytelling unless we are actually telling a story. It all starts with being able to tell the difference between a story and everything else. We call that story spotting. It’s the foundation skill.

A vast array of businesses already invest in story techniques. And many have developed capabilities across the areas we described. They are becoming story-powered organisations where humanity is front-and-centre offering a new competitive advantage: one where there is meaning; one where there is progress; one where people truly care.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Shawn Callahan, Mark Schenk, Mike Adams, and Paul Ichilcik are the principals of Anecdote International and together have delivered all of the corporate storytelling initiatives described above. They are best-selling authors, expert facilitators and world-leading thought leaders on corporate storytelling. You can contact them at www.anecdote.com.